CD Gallery: click on the CD to read the reviews

Robert Maxham - Fanfare Magazine

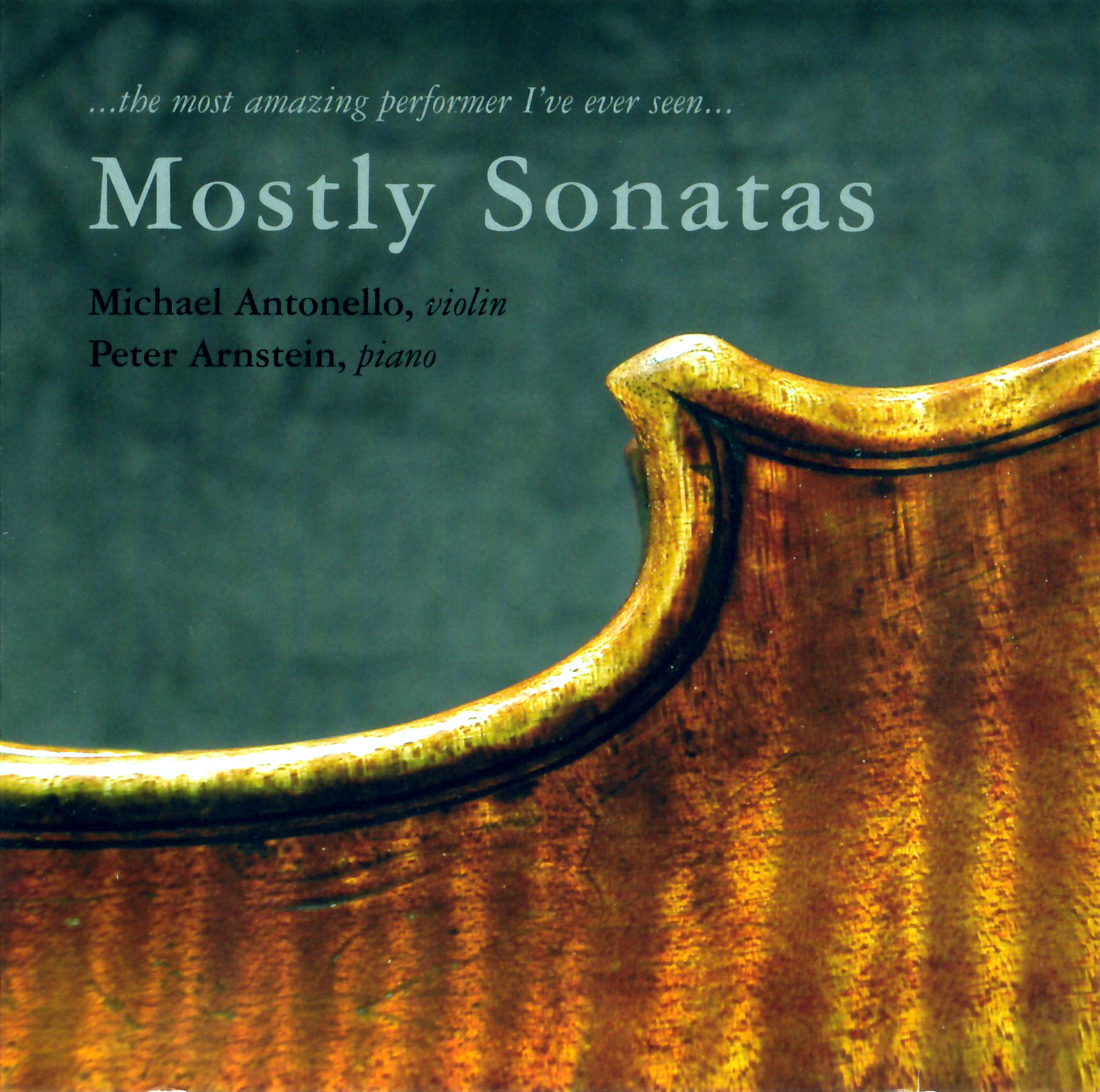

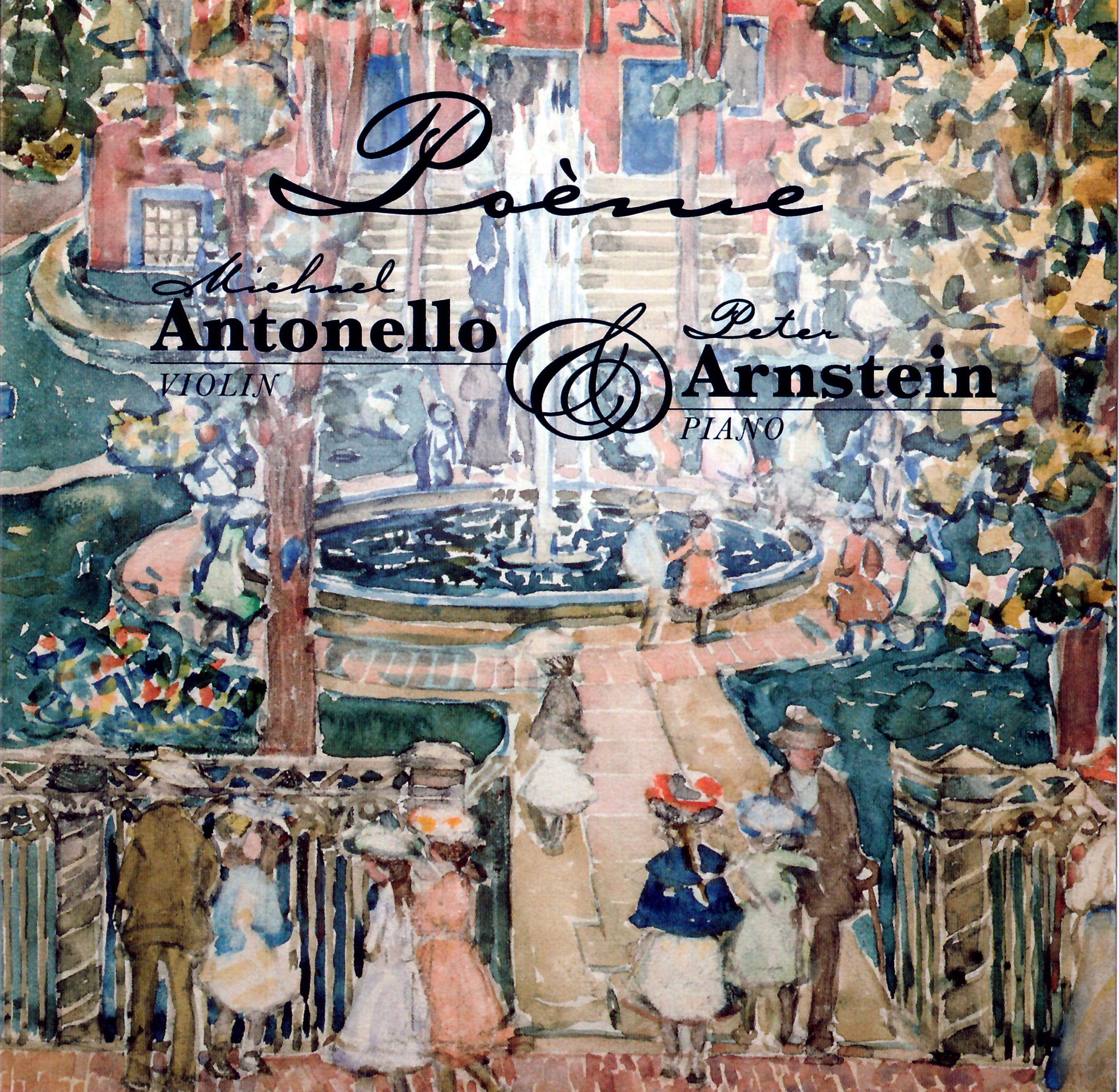

MOSTLY SONATAS • Michael Antonello, vn; Peter Arnstein, pn. • MJA 00 ( 73:28)

KREISLER Tempo di minuetto. BRAHMS Violin Sonata No. 3. ELGAR Chanson di matin. DEBUSSY Violin Sonata. SCHUMANN (arr. Kreisler) Romance. FRANCK Violin Sonata

Violinist Michael Antonello follows in the footsteps of Charles Ives in making his living by providing financial services; but both his education at the Curtis Institute and Indiana University and the technical polish and sensitive nuance of his playing bespeak an assurance that, like Ives's, makes his musical statements coherent and his communication convincing. In collaboration with pianist Peter Arnstein and sound engineer Tom Mudge, he has created a sumptuous showcase for his recently acquired 1720 ex-Rochester Stradivari, a violin with a strong tonal profile that Antonello deploys with the familiarity of a longer association. Interspersing short pieces with sonatas from the standard repertoire relieves the program of typical sonata-recital severity—yet without introducing mindless bravura characteristic of so many virtuoso showpieces. Antonello hardly eschews the elegant porta-mentos that imparted to the performances of earlier violinists a uniquely personal stamp. These appear in the opening Kreisler bon-bon, but insinuate themselves even more ingratiatingly into the denser textures of Brahms's Third Violin Sonata. In that Sonata's slow movement, his violin and its distinctively rich (yet reedy) tone, especially on the G-string, claim almost equal partnership with the violinist and pianist themselves. But the duo's timbrai lushness finds cogent complements in the third movement's rhythmic piquancy and in the finale's ardor.

Edward Elgar spent decades as a violinist and graced the instrument's repertoire with a number of miniatures (as well as the Concerto and Sonata) that, except for a small number of popular ones like Salut d'amour, have received only sporadic attention. The contrast of the duo's chasteness in the Chanson di matin with their gauzy sensitivity in the first measures of Debussy's Sonata also contrasts the silvery brightness of the ex-Rochester's middle and upper registers with the suggestivity of its lower ones. Antonello's approach resembles Oistrakh's opulent richness rather than Szigeti's thoughtful leanness, though he brings high resolution to the tantalizingly elusive figuration in the Intermède and builds the finale to a satisfyingly dramatic conclusion. He strops the edges of Schumann's Romance, which might have been left blurred and indistinct, incidentally—although perhaps not inadvertently—enhancing the music's urgency as well as its focus. If Arnstein doesn't linger in the shadows of Franck's opening ninth chords, he plays the rippling figuration of the Allegro that follows with an etched clarity that makes their forward momentum all the less resistible—Antonello and Arnstein soar in this movement with a rhapsodic ecstasy reminiscent of Stern and Zakin's. If the canonic finale's rapt mysticism has come to sound disappointingly perfunctory in many performances, it soars in Antonello and Arnstein's intense reading.

Robert McColley recommended a recording of trios by Antonello and Arnstein, with cellist Scott Adelman, released about the same time, in 29:1. In these engaging sonata readings by partners that consistently fire on all cylinders, in recorded sound that holds the instruments in dynamic balance and represents the full timbrai range of each (the violin as an instrument has hardly ever been represented in so flattering a portrait), of repertoire that offers stimulating diversity as well as profound communication, Antonello and Arnstein's recital can hardly fail to make a strong impression on all types of listeners. Correspondingly strongly recommended.

This article originally appeared in Issue 29:2 (Nov/Dec 2005) of Fanfare Magazine.

Want List for Robert Maxham - Fanfare Magazine 2005

The Want List for 2005 features mixtures of the present and the past in various proportions. The re-release of Louis Kaufman's premiere recording of Vivaldi's Cimento serves as a reminder that the work's excitement depends more on the performer's enthusiasm and artistry than on that advocacy's specific stylistic language. Similarly, if Heinrich Biber's Rosary Sonatas, which once occupied a bibliographic position on the fringe of the violin's repertoire, move even closer than they have to the center, appealing at last to general audiences, that transition should result in no small part from Andrew Manze's nearly hypnotic projection of their mystical aura. My father, who heard David Rubinoff in the 1930s, remarked that listening to Zino Bogachek's réanimation of remains buried in stacks of out-of-print sheet music was like “renewing an old acquaintance.“ Michael Antonello's collection of sonatas and short pieces creates a similar impression of meeting old friends in fresh, elegant surroundings. And Bein and Fushi's combination of five DVDs with a CD of some of Ricci's best performances both demonstrates what he achieved and provides a unique insight into the way such an artist understands and transmits that achievement to future generations.

Want List 2005

BIBER Rosary Sonatas. Passagalia • Manze Egarr McGillivray • HARMONIA MUNDI HMU 907 321/22

MOSTLY SONATAS • Antonello Arnstein • MJA Works by KREISLER, BRAHMS, DEBUSSY, SCHUMANN, FRANCK

MAESTRO RUGGIERO RICCI: THE VIOLIN VIRTUOSO OF THE 20TH CENTURY • Ricci • NO LABEL 00 (5 DVDs; Encore CD) www.beinfushi.com

DAVID RUBINOFF—TANGO TZIGANE • Bogachek Balakerskaia • VERNISSAGE VR 9706

RUBINOFF Mon reve d'amour. Fiddlin' the Fiddle. Tango tzigane. Stringing Along. En el jardin espagnol. Banjo Eyes. Gypsy Fantasy.

Rubinoff transcriptions of DEUTSCH, CARMICHAEL, BERLIN, TRAD, ARLEN, ELLINGTON

VIVALDI Il Cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione. Concerto for 2 Violins in D • Kaufman Rybar Swoboda Concert Hall CO Dahinden Winterthur SO Zurich • NAXOS 8.110297

This article originally appeared in Issue 29:2 (Nov/Dec 2005) of Fanfare Magazine.*

Jeffrey J. Lipscomb - Fanfare Magazine

MOSTLY SONATAS • Michael Antonello, vn; Peter Arnstein, pn. • MJA 00 (74:07).

At first glance, the title “Mostly Sonatas“ appears to be mathematically challenged, for there are exactly three sonatas and three other works here. But the non-sonata pieces by Kreisler, Elgar, and Schumann consume only 15 percent of the disc's playing time, so the title is accurate in that regard. This CD by violinist Michael J. Antonello is on his own label (MJA, no disc number), and he is joined by fellow Minnesotan Peter Arnstein, who teaches piano and composition at the St. Paul Conservatory. Antonello happens to be a life insurance salesman by trade, so obviously the violin is not his whole life (sorry, I couldn't resist the pun). But he is Curtis-trained and has served as concertmaster in two regional orchestras. Antonello plays on his own 1720 Stradivarius here.

Tempo di minuetto is one of several works Fritz Kreisler wrote “in the style of other composers (Pugnani in this case). This reading by Antonello is utterly charming, and he's well supported by Arnstein. Elgar's Chanson de matin is salon music of a pleasant stripe that's heard more frequently in an arrangement for string orchestra, although British violinist Arthur Catterall recorded it on 78s with an unnamed pianist. The account here is altogether beguiling. Debussy's Violin Sonata comes from 1917, when the composer was dying of cancer, and it's one of his most magical works. While I could never give up the classic 1940 live account by Szigeti with Bartók (Vanguard), this one certainly has better sound and is very stylish in its own right.

The Franck Sonata, my favorite work by that composer, is given an eloquent and poetic reading, somewhat in the laid-back manner of the 1934 Spalding/Benoist (a deleted CD from A Classical Record). Antonello and Arnstein don't sound as Gallic as the Thibaud/Cortot (a 1923 acoustic with fierce sound formerly on Biddulph; I think it's better than their 1929 account on Strings). But frankly, I still prefer the more galvanized live 1947 reading by Taschner and Gieseking (Bayer), not to mention my “desert island” choice: the superbly impassioned 1966 live Oistrakh/Richter (on a disgracefully deleted BMG Melodiya five-CD set). The latter set also contains an Oistrakh/Richter Brahms Third Sonata that's far more bold and dramatic than what Antonello and Arnstein provide here, and an Oistrakh/Makarov account of the Schumann Romance that's incomparable. In the Brahms, I also treasure Szigeti/Petri (Andante) and De Vito/Fischer (Testament).

Of course, all those cited favorites are in older sound, and several of them are out of print. I am keeping this MJA disc mostly for the Kreisler, Elgar, Debussy, and the Franck. This CD is recommended to: (1) those who want music by these six composers on a single disc (so far as I know, it's unique in that respect); (2) collectors seeking rarely recorded music (the Kreisler and Elgar); and (3) listeners who prefer their chamber music in a mostly understated vein with good modern sound.

This article originally appeared in Issue 29:2 (Nov/Dec 2005) of Fanfare Magazine.

Lynn René Bayley - Fanfare Magazine

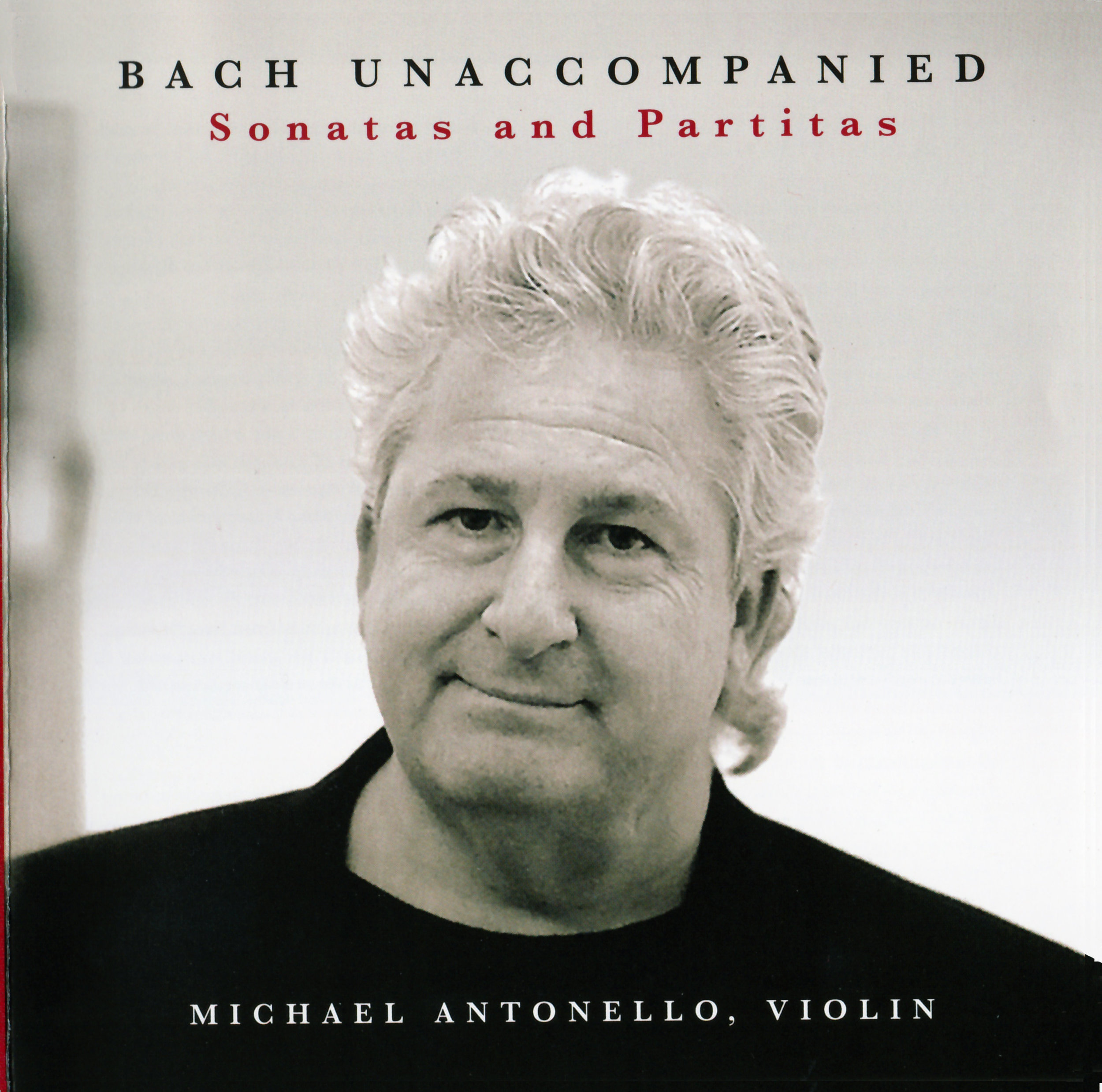

BACH Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas • Michael Antonello (vn) • MJA PRODUCTIONS 707541548892 (2 CDs: 135:29)

Michael Antonello, who judging by the liner notes has left his position(s) as a player in the Rochester Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, and St. Paul Chamber Orchestra to pursue a solo career, here presents us with his vision of Bach’s unaccompanied violin music. Playing a 1742 Guarnieri del Gesù instrument, he produces an exquisite tone and has exemplary bowing technique, and his interpretations are both tasteful and played with tremendous feeling. Antonello’s stated approach towards these works is to “play all of the notes with a beautiful sound, excellent intonation (pitch), and relentless steady rhythm. This is difficult to accomplish,” he adds, but this he most certainly does, aided in the selection of different takes for this issue by his violin-playing sister, Cara Mia Antonello.

My lone caveat regarding these performances is something that Antonello feels is a virtue, the “relentless (emphasis mine) steady rhythm.” For my taste this only works in a few movements, such as the famous Prelude to the E-Major Partita. I’m happy to say, however, that Antonello is not consistently relentless—he relaxes the rhythm somewhat in the slow movements, particularly the Sarabande of the D-Minor Partita, with fine results—but this is certainly a reading in strict time, much like Nathan Milstein’s famous 1950s recording of the cycle for EMI. Thus I can understand those who would appreciate this kind of interpretation and would therefore recommend it to those listeners. Despite being recorded in three separate venues with differing sonics, Antonello and his engineers have done an excellent job of retaining consistency of sound.

Jerry Dubins - Fanfare Magazine

BACH Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas • Michael Antonello (vn) • MJA PRODUCTIONS 707541548892 (2 CDs: 135:29)

Michael Antonello, by his own admission, is not a professional violinist, which, in common parlance is taken to mean one who does not earn his or her living as a performing artist. But following a career path in life other than that of a professional performing artist is not necessarily a measure of one’s musical abilities or dedication to the art. In fact, when it comes to training and experience—study under Joseph Brodsky at the Curtis Institute, then with Franco Gulli at Indiana University, followed by invitations and appointments to play in numerous professional ensembles—Antonello is not someone who just picked up a violin one day and decided, out of vanity, to learn and record major works from the violin’s mainstream repertoire.

In fact, he is a man of deep humility, a man ever striving to better himself and to make the very best of the considerable technical skills and musical gifts with which he has been endowed. This became clear in a phone conversation I had with Antonello a while back in which he shared with me that more than anything else he wishes his recordings to be a legacy by which he’s remembered by family descendants and friends.

Antonello’s hard-earned technical facility on the violin, coupled with his unerring musical instincts, has more often than not resulted in near topflight professional performances. But it’s the “near” that has made it difficult to review some of Antonello’s earlier recordings in Fanfare, a publication whose readers expect contributors to make comparisons and recommendations from among countless performances of a work by the world’s greatest players, past and present; and again, in our conversation, Antonello acknowledged that he does not consider himself to be in the same league as a Heifetz or a Milstein. That is part of the man’s modesty and humility, and had you asked me what I thought based on hearings of Antonello’s previous recordings, I would have said that it wasn’t false modesty that he was expressing. But his latest release of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin is a real game-changer.

Sooner or later, most violinists decide to have a go at this monument to the art of music for solo violin, with results that have not always been edifying. It has to be acknowledged that Bach wrote these works for the violin he knew, not for the violin of 100 years later. Thus, approaching these works on a modern instrument has always required compromises in the way chords are broken and bowed due to the greater curvatures of the fingerboard, bridge, and bow and the increased tension on the strings. On the other hand, realizing these works on a period instrument may abate those particular problems for the player, while raising the specter of compromised intonation and tonal allure for the listener.

It also has to be acknowledged that Bach’s solo violin works did not arise out of thin air; they are the culmination of a German tradition of experimental speculation in the seemingly improbable possibilities of a non-keyboard instrument engaging in counterpoint with itself. One has only to look to the solo violin works of Heinrich Ignaz Biber (1644–1704) to discover the ancestry of Bach’s solo sonatas and partitas.

Antonello performs these formidable works on his prized 1742 Guarneri del Gesù, which, of course, is set up, strung, and tuned according to modern standards. Before going further, a few words on the recordings themselves are in order. They were made in three different venues between July 2011 and June 2012. Antonello’s sister, Cara Mia Antonello, herself an accomplished violinist, spent many hours listening to and assisting in the editing of these performances, while lead sound engineer Ryan Albrecht and co-engineer Tom Mudge of Senyah Sound insured that optimum advantage was taken of the acoustic properties of each the recording sites. The First and Third sonatas were recorded in Chicago’s St. Paul’s Church; the first, second, and fourth movements of the D-Minor Partita were recorded in Chicago’s Hemingway Museum in Oak Park Heights; and everything else comes from the Unitarian Church in Mahtomedi, Minnesota. No matter, for so superb a job of equalizing and balancing have the engineers done that you wouldn’t know that the fifth movement of the D-Minor Partita (the great Chaconne) had crossed two state borders.

Now, speaking of the Chaconne, that’s where many a critic would begin his or her review, but not this one; it’s too easy a place to start and, besides, for all its majesty, the Chaconne is actually not the most technically challenging movement among the six works. Stamina and endurance it takes, no doubt, but the most difficult movements are the massive fugues in each of the three sonatas in which concentrated, rigorous, and intensive double- and triple-stopping is pervasive and for long stretches virtually unalleviated.

But there is yet another tough challenge that comes in the third movement of the Second Sonata, and it’s a problem related more to bowing than to fingering. In Bach’s day and on a violin of the period with a flatter bridge and a bow more adapted to the relational height of the strings, it wouldn’t have posed such difficulty. But with a modern instrument and bow the player needs to create the impression that the bow is made of rubber. The technique is referred to as the louré or portato stroke, and to play what Bach wrote requires that a note on one string be held while the bow dips down intermittently to play notes on the string below, while the upper note continues to sound without interruption and without accent. Perhaps I marvel at those who can do it at all (I never could master it), let alone do it smoothly and expressively. This is the first test to which I put any player of the sonatas and partitas, and Antonello passes it with flying colors.

Discretion being the better part of valor, Antonello takes all movements, not just the fast ones, at a somewhat more leisurely pace than we tend to hear them from today’s power players. But what may be lost in the “Flight of the Bumblee” contest of “I can play it faster than you can” in movements like the perpetual motion Preludio of the Third Partita, the Presto of the First Sonata, and the concluding movement of the Second Sonata is more than compensated for in sureness of fingering and bowing, trueness of intonation, expressiveness in dynamics and phrasing, and a buttery smoothness of rich and vibrant tone pouring forth from Antonello’s magnificent del Gesù violin. Moreover, Antonello demonstrates a solidity and evenness of tone production that allows each tone within double- and triple-stops to be equally weighted and to guide the ear infallibly from one harmonic tension and its resolution to the next. This is particularly welcome in the fugues, where “counterpoint,” as such, is sometimes more virtual than actual and can seem a bit wayward when the underlying harmony isn’t clarified in the way that Antonello brings it into focus.

And what of the Chaconne? Well, as indicated above, Antonello’s tempos in general tend to feel unhurried, and that applies to his reading of the Chaconne as well. He allows it to unfold in large periods, rather than calling undue attention to the regularity of the eight-bar variation structure, which, when emphasized as it is by some players—Alina Ibragimova, comes to mind—can make the piece seem a bit choppy. In Antonello’s hands, it feels almost as if the Chaconne is finding its own tempo and its own way of telling. After arriving at my conclusion, strictly by listening, that Antonello’s Chaconne was comparatively on the measured side, I decided to do some checking against other versions in my collection, and it turns out that I was doubly surprised, first, because Antonello is not as leisurely as I thought—among 17 performances, his is number nine, placing it almost exactly midway between the slowest and the fastest—and second because the players I expected to be the fastest were not necessarily so. Here are the results in order of fastest to slowest.

Josef Silverstein 12:41

Jascha Heifetz 1952, mono, RCA 12:56

Arthur Grumiaux 13:14

Nathan Milstein (1973. Deutsche Grammophon) 13:55

Henryk Szeryng (1954, mono, CBS/Sony) 14:00

Alina Ibragimova 14:10

Henrk Szeryng (1968, Deutsche Grammophon) 14:23

Yehudi Menuhin (1935, mono, EMI) 14:43

Antonello 14:50

Gregory Fulkerson 14:56

Dmitry Sitkovetsky 15:04

Uto Ughi 15:24

Perlman 15:46

Julia Fischer 15:47

Sergey Khachatryan 16:25

James Ehnes 16:41

David Grimal 16:44

I guess the four that surprised me the most were Milstein, who I expected to be in first or second place for fastest, Grumiaux, who I would not have expected to be as fast as he is, and both Julia Fischer and James Ehnes, neither of whom would I have expected to be among the slowest. But there you have it. So, at least in the Chaconne, Antonello is right behind Menuhin and Szeryng’s 1968 remake, the latter, my longtime favorite and first choice in the Bach Unaccompanied Sonatas and Partitas. Not bad company to be in, I’d have to say. Antonello’s performances of these works are, in my opinion, among the very best of the best, and for anyone who is passionate about Bach and the violin they deserve your urgent attention.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

BACH Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas • Michael Antonello (vn) • MJA PRODUCTIONS 707541548892 (2 CDs: 135:29)

These sonatas and partitas for unaccompanied violin are at the pinnacle of the violin literature. They demand the utmost in technical proficiency as well as the ability to make Bach’s beautiful melodies sing. Michael Antonello has waded into deep water and on this disc he proves he can swim with the big fish. In the G-Minor Sonata he takes a lyrical approach that shows the beautiful tones he can draw from his instrument. He begins the Fuga somewhat slowly and lets it build up to full speed. Bach’s melodic Siciliana makes me wonder if the German composer ever thought of what life could be like in a warmer climate. He certainly imbued this segment with musical warmth. Antonello plays it with a wondrous array of tonal colors and follows it with a furious, but always technically correct, Presto. The partitas are more freely constructed than the sonatas and the commonly heard movements were originally dances. In 1732 Johann Gottfried Walther wrote in Leipzig’s Musikalisches Lexicon that the Allemanda “must be composed and likewise danced in a grave and ceremonious manner.” The Sarabande was brought from 16th-century Central America and at one time was thought to be obscene. The Corrente provided a lively change of pace from the many slow dances. Tempo di Borrea is an Italian term for the more usual Bourrée, here a catchy dance from France and Spain.

In the B-Minor Partita each of these dance movements is followed by a “double,” a set of variations which Antonello plays with flawless intonation and flexible phrasing. The Sonata in A Minor is more strictly constructed and Antonello plays it with an abundance of strength and control. He gives a bravura performance in the Fuga, although his highest tones sometimes grow a bit thin. In the Andante, however, he provides an exquisite melodic meal for hungry listeners. Bach composed his works for solo violin between 1703 and 1720 and he may have written the Ciaconna, the last movement of the D-Minor Partita, to honor his first wife, Maria Barbara, who died in 1720. If true, it is a touching memorial to the mother of Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel. The C-Major Sonata and the E-Major Partita are the only pieces on this two-disc set that are not in minor keys. The C Major starts with a pleading Adagio followed by a charming Fuga that has powerful double-stopping played in strict rhythm. Its Largo treats us to a long melodic line punctuated with perfect trills that sound easy when this violinist plays them. The finale to this wonderful piece is a sunny melody that refreshes the soul with virtuoso playing. Antonello plays the familiar Preludio of the E-Major Partita at a moderate speed that leaves room for both faster and slower tempos to follow. The melodic Loure sings directly to the heart while the even more familiar Gavotte makes every listener want to dance. This is Bach at his happiest, perhaps enjoying his children at play. His menuets are short and his final Gigue is an excellent showpiece for the virtuoso violinist. Antonello is thoroughly at home in it. There are many other versions of this music, among them Henryk Szeryng’s performance on Deutsche Grammophon. Arthur Grumiaux plays these pieces on Philips, Gidon Kremer on ECM, and Isabelle Faust on Harmonia Mundi. All of them play impeccably, but there are vast differences in interpretation. If you like an older style of playing, Szeryng or Grumiaux might be your choice, but you may have to deal with lesser sound quality than you get on a newer disc. Kremer’s tempos are somewhat unorthodox, but he has a modern take on Bach. Faust plays well but does not embellish as much as some listeners might like and the sound on her 2010 disc is not as good as it should be. I enjoyed Antonello’s CD because he is a fine virtuoso who plays with consummate style and the ambient sound makes me think I am in a small concert hall with excellent acoustics.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

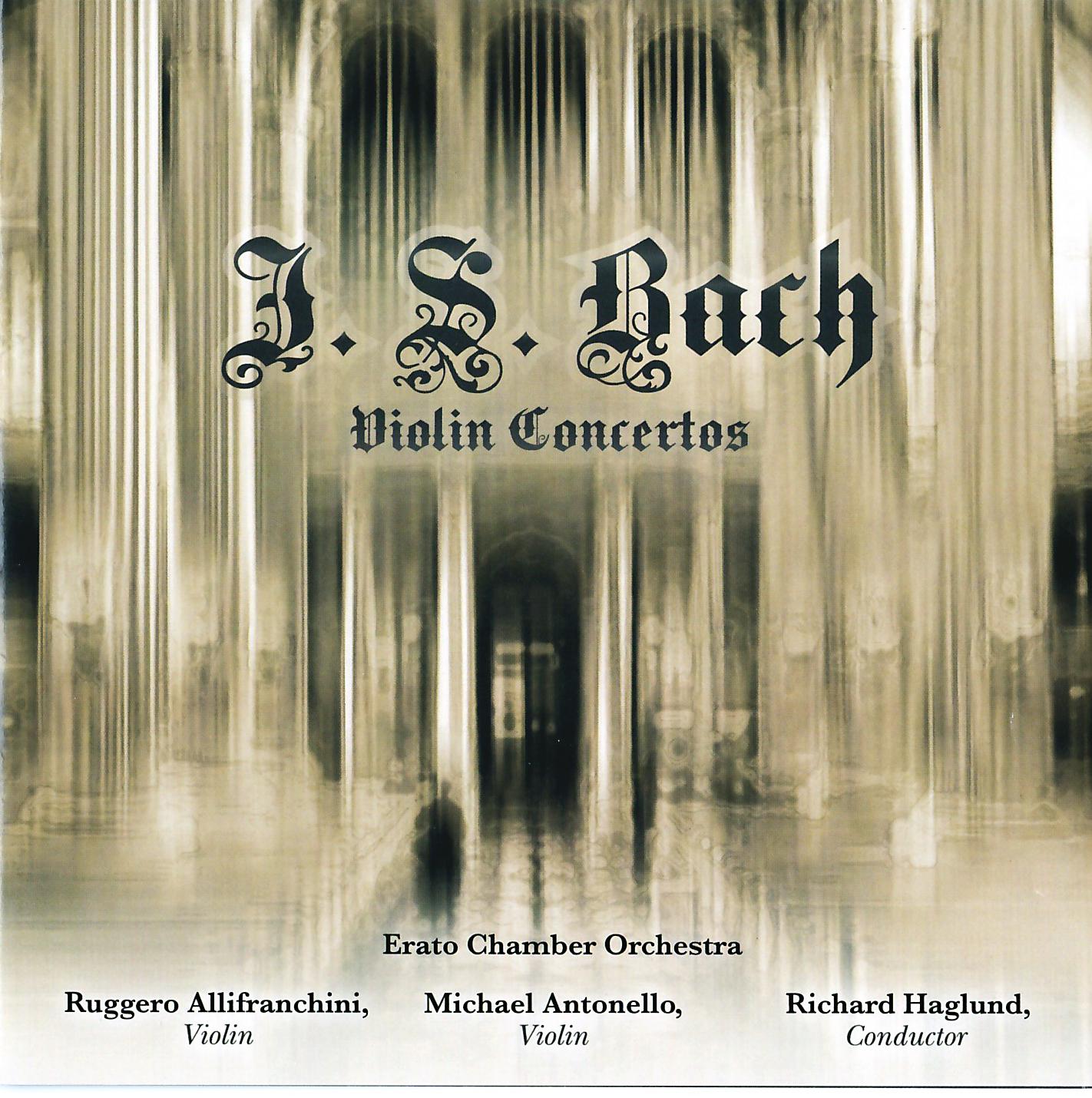

BACH Violin Concertos: No. 1 in a; No. 2 in E. Double Concerto. Orchestral Suite No. 3: Air (arr. Arnstein) • Michael Antonello, Ruggero Allifranchini (vn); Richard Haglund, cond; Erato CO • MJA no catalog number (52:44)

Bach probably composed his Violin Concerto in A Minor, BWV 1041, and his Concerto for Two Violins, Strings, and Continuo in D Minor, BWV 1043, between 1717 and 1723. Most likely he did not write the Violin Concerto in E Major until 20 years later, but he must have been very satisfied with it because he reused it as the model for his Harpsichord Concerto in D Major. Michael Antonello, who has successfully recorded many of the great masterworks for violin, has finally given us a disc of Bach’s music. Maestro Richard A. Haglund, the founder and music director of Chicago’s Erato Chamber Orchestra, leads its excellent musicians in bravura renditions of Bach’s technically challenging music. Antonello plays the allegro movements fast and some of his top notes in the first concerto tend to be a bit wild, but the emotion with which he imbues his slower movements makes this long-time listener reach for a handkerchief. On his wonderful Guarneri del Gesù violin, he captures something quite special in these movements. Antonello and St. Paul Chamber Orchestra associate concertmaster Ruggero Allifranchini execute the Double Concerto with radiant tone colors and flawless precision. They don’t play it at breakneck speed. Instead, they show us some of the beauty that is missing when the music is played too fast. There are several recordings of these three concertos by much better-known soloists, and much of the music is played in a manner that allows the violinist to show speed and virtuosity. Hilary Hahn plays them at a fast pace on a Deutsche Grammophon 2003 recording. Julia Fischer’s tempos are even faster on her 2009 Decca disc. Both of them miss out on the possibility of charming the listener with the more introspective aspects of Bach’s music. Daniel Barenboim conducts Itzhak Perlman’s 2002 EMI recording of the three concertos and the second violinist for the Double Concerto is Pinchas Zuckerman. That disc is the most serious competition for any Bach recording, but it is also closest to Antonello’s in musical and emotional appeal.

Antonello concludes his recording with a delightful rendition of Bach’s Air on a G String. The piece is actually an arrangement of the Air from Bach’s Overture No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068, originally written sometime between 1717 and 1723. German violinist August Wilhelmj named it after he transposed the piece from D Major to C Major and took it down an octave. He then found that he could play it on one single string of his violin, the G string. Peter Arnstein, who wrote the informative booklet, also arranged the work for violin and orchestra. He takes it back to its original key and Antonello makes it pull at the listener’s heartstrings. It’s a charming way to end this fascinating disc, which has excellent sound as well as fine work by all the artists who perform on it.

Want List for Dave Saemann - Fanfare Magazine

I enjoyed Michael Antonello’s traversal of Bach’s violin concertos as much as any CD this year. Antonello’s playing features a wonderful blend of strength and tenderness, highly suited to the breadth of emotion in Bach. His partnership with Ruggero Allifranchini in the Double Concerto showcases differing yet complementary styles and instruments, resulting in one of the truly great renditions of this score. The CD concludes with Peter Arnstein’s lovely arrangement of the Air from Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite for solo violin and strings, with Antonello demonstrating exceptional but uncloying warmth. I’ve reviewed a number of outstanding Brahms recordings this year, but my favorite is Simone Young’s version of the last two symphonies. Her readings are filled with passion and vibrancy, yet with all the thoughtfulness and stylishness one could wish for. The Hamburg Philharmonic gives Young playing that is highly distinctive in its Central European sound, a real throwback to the orchestral tone from German recordings between the wars.

The first releases from the Seattle Symphony under Ludovic Morlot include an all-American album that shows the orchestra in luminous form. The centerpiece is a performance of Ives’s Second Symphony that places it squarely within the European symphonic tradition. It may not please listeners who like a more folksy interpretation of the work, but Morlot conducts it with discretion, splendid forward momentum, and a superb sense of proportion. Among historical reissues this year, I heard none more important than Pristine’s CD devoted to the music of Harl McDonald. The influences here on McDonald’s compositions are manifold: Hebrew, African-American, Latin, folk song of the American West, and English ballads. Yet everything comes out sounding like Harl McDonald—good-natured, genial, Romantic, and beautifully orchestrated. Finally, Frans Brüggen’s live account of the last three Mozart symphonies gives us period instrument performances that rival the finest versions from the past. Brüggen’s Mozart has freshness, style, warmth, and tenderness.

Want List

BACH Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2. Double Concerto. Air • Antonello, Allifranchini / Haglund / Erato CO • MJA

BRAHMS Symphonies Nos. 3 and 4 • Young / Hamburg PO • OEHMS 677 (SACD)

IVES Symphony No. 2. CARTER Instances. GERSHWIN An American in Paris • Morlot / Seattle S • SEATTLE SYMPHONY MEDIA 1003

MCDONALD Symphony No. 1. Two Hebraic Poems. Cakewalk. San Juan Capistrano. Rhumba. Dance of the Workers. The Legend of the Arkansas Traveler. From Childhood • Phillips,Ormandy, Koussevitzky,Stokowski,McDonald / Philadelphia O, Boston SO • PRISTINE 402

MOZART Symphonies Nos. 39-41 • Brüggen / O of the Eighteenth Century • GLOSSA 921119 (2 CDs)

Dave Saemann - Fanfare Magazine

BACH Violin Concertos: No. 1 in a; No. 2 in E. Double Concerto. Orchestral Suite No. 3: Air (arr. Arnstein) • Michael Antonello, Ruggero Allifranchini (vn); Richard Haglund, cond; Erato CO • MJA no catalog number (52:44)

BRAHMS Violin Sonatas Nos. 1–3. Sonatensatz • Michael Antonello (vn); Peter Arnstein (pn) • MJA no catalog number (71:13)

VIVALDI The Four Seasons. PUCCINI (arr. Arnstein) Opera Medley. BACH Partita No. 2 for Unaccompanied Violin: Chaconne • Michael Antonello (vn); Peter Arnstein (pn); Richard Haglund, cond: Erato CO • MJA no catalog number (69: 43)

The late conductor James Sadewhite said that there are many great players, but only a few get to become famous. Michael Antonello is a great player whom fame unaccountably has passed by. What makes Antonello a great artist? He certainly has plenty of technique, plus a wonderful understanding of the possibilities inherent in the fine instruments he plays. Antonello’s performances are imbued with a warmth and directness that seem to come straight from his personality. I once had a piano teacher who said she wished she had played the violin because one can express oneself more completely and with more intimacy on that instrument. It is fair to say that we know a lot about Michael Antonello the man from the way he plays the violin. That being said, Antonello also is a stylistically accomplished musician, able to adapt his playing to the sensibility of whatever composer he is interpreting. He also has tremendous imagination, with a feeling for fantasy that enables him to unlock the hidden meanings in whatever music he tackles. My editor informs me that other life commitments are leading Antonello to leave the music business. This saddens me terribly. Fortunately, Antonello’s playing is well documented on CD. The present three albums rank with the finest recordings of these works that I know.

In the opening movement of Bach’s First Violin Concerto, Antonello is plain spoken and even a little gruff—a reminder that Bach was solidly a member of the bourgeoisie. In the Andante, Antonello evokes a pastoral idyll, with more than a little touch of Vivaldi. The rich tone colors of his Guarneri del Gesù are more akin to those of an oil painting than a pastel. He plays the concluding movement as a dance like a bergamask, achieving rhythmic exactness while maintaining a rich tone. In the Second Concerto’s Allegro, Richard Haglund’s excellent Erato Chamber Orchestra matches Antonello for beauty of tone. Antonello mines the movement’s coloristic possibilities like an aria for vocal display. He plays the Adagio in the style of Bach’s music for solo violin, with the orchestra gently filling in the harmonies. He gives the last movement the feeling of a caprice.

The Double Concerto here is very special. Ruggero Allifranchini is a former member of the Borromeo String Quartet and an accomplished chamber music player. His Stradivarius forms a contrast and a splendid complement to Antonello’s Guarneri. In the opening Vivace, the orchestra is caught up in the excitement from the start. The tone quality of the violins together is like an excited conversation. Allifranchini plays with simplicity and limpid sound that match Antonello well. The slow movement convinces me that the soloists have heard the older recordings of Fritz Kreisler and Efrem Zimbalist. Allifranchini and Antonello here offer a seminar on all the tonal possibilities of two violins playing together. Antonello’s shrewd decision to take the second violin part permits his Guarneri to fill out the lower sonorities between the two violins. In the concluding Allegro, the virtuosity of all concerned throws off sparks. The soloists in it are like two great dramatic actors performing a climactic scene. Peter Arnstein has arranged skillfully the Air from Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite for solo violin and strings. Antonello gives it a gentle, Romantic performance, which is a textbook on style. This CD’s sound engineering is a model of what digital recording should be: warm, well balanced, and clear. I have a soft spot for the deeply Romantic 1958 recordings of the concertos by Roberto Michelucci and I Musici, with Felix Ayo in the Double Concerto. Michelucci performs in the style of the great violinists of an earlier generation, conjuring up Elman-like tone. I also enjoy the Double Concerto as played by Jascha Heifetz and Erick Friedman. Antonello’s album is the best digital recording I know of these works.

From Vivaldi to Puccini is an excellent idea for an album, as both composers share an Italianate sense for melody. Antonello welcomely precedes each of the concertos in The Four Seasons with a recitation in English of the poems in the score, a throwback to the wonderful old Max Goberman LP that included the poems in Italian as a postlude. Antonello plays “Spring” with zest. His dialogue with the concertmaster is especially vivid. The Largo has restless energy. Antonello lets you feel the unease of “Summer,” while the orchestra creates beautiful washes of sound. In “Autumn,” the soloist’s playing is earthy, with double stops that almost growl. Haglund gets an edgy yet rich tone out of his orchestra in “Winter.” Antonello’s performance in it is quicksilver. My favorite Four Seasons is on a beautiful-sounding Vox LP by Susanne Lautenbacher with Jörg Faerber, which also has been on CD. Of other recordings, I do have a slight preference over Antonello’s for the one by Takako Nishizaki with Stephen Gunzenhauser, a reading of great charm. Peter Arnstein’s arrangement of arias from La bohème and Gianni Schicci is very fine. He reorders the Bohème material for greater variety, while the transition to “O mio babbino caro” is magical. Antonello plays the medley with appealing tenderness. The recording of Bach’s Chaconne is new, not the one Antonello included in his set of the complete Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. The rendition possesses glowing tone and excellent attention to structure. Antonello is passionate without ever going over the top. In this performance, the music seems timeless and eternal, rather than belonging to any specific period. The recording is a touchstone for this work. The sound engineering throughout From Vivaldi to Puccini is excellent.

The Brahms sonatas album is a compilation from previous releases. One can take Antonello’s excellence here for granted, but what a marvelous Brahmsian Peter Arnstein is! He plays with a light touch and produces a warm, unforced tone perfectly suited to Brahms’s thoughtful Romanticism. Arnstein delineates structure marvelously, while never overlooking attention to detail. His musicianship possesses a sense of reflection that makes every moment in Brahms come alive. Arnstein also is a splendid collaborative artist. His partnership with Antonello is hand in glove. The opening movement of their First Sonata features a grand sweep, incorporating both tenderness and majesty. Antonello plays the Adagio with a tonal subtlety filled with inference. In the last movement, both players convey a delicious unease while making a beautiful sound. For the opening movement of the Second Sonata, the musicians realize the Amabile marking with a sweet and sinuous rubato. Antonello depicts yearning in the slow movement with directness and a pure tone. Playing on a Stradivarius, he makes a rich sound in the concluding movement.

Back in the 1970s, I heard the Third Sonata played in recital by Isaac Stern with David Golub and by Nathan Milstein. Both violinists produced a more opulent tone than Antonello, but neither gave a rendition more penetrating. Antonello and Arnstein are marvelously incisive and rhythmically deft in the opening Allegro. In the Adagio, Antonello displays a noble stoicism. Both players produce an unusual range of colors in the third movement. Their concluding movement resembles a philosophical dialogue between the instruments. For the Sonatensatz, composed when Brahms was 20, the performers demonstrate an appropriate youthful energy and a questing spirit. The sound engineering on the album ranges from very good to superb. My favorite CD of the sonatas is the rather more controlled account by Curtis Macomber and Derek Han. Another recording worth drawing attention to is by the late Eugene Fodor and Alexander Peskanov. Fodor was typecast as a player of showpieces, and his Brahms is a little stiff in places, but there are many touching moments. Antonello and Arnstein’s version is rewarding in its own way and shows absolute commitment. I have enjoyed following Michael Antonello on his journey through the violin repertoire. I hope that his dedicated artistry brings him many admirers. He is one of the true musicians on his instrument, and never has disappointed me in his endeavors.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

BRAHMS Violin Sonatas Nos. 1–3. Sonatensatz • Michael Antonello (vn); Peter Arnstein (pn) • MJA no catalog number (71:13)

Johannes Brahms wrote the three sonatas on this disc during the height of his popularity. The 1868 premiere of his German Requiem confirmed his reputation as the most popular composer of the time and gave him the confidence to complete a number of works that he had wrestled with over many years. This recording opens with his Sonata No. 1, op. 78. Violinist Michael Antonello and pianist Peter Arnstein begin with a light and airy approach that brings thoughts of a sunny spring afternoon. The breeze strengthens and a rain cloud waters the new buds, but the sun returns as violinist and pianist revert to their original tempo. The second movement contains one of those melodies that is unique to Brahms and here it touches your soul. Antonello does his finest playing in slow movements and this Adagio shows him at his best. Although the final movement is faster, it still has the bittersweet quality of the memory of a long-past love affair. Since the Second Sonata, op. 100, is open to dramatic interpretation, Antonello and Arnstein grasp the first movement and give it a wide dynamic range. The following Andante invokes tranquility and even with its three intrusions of liveliness, it is wonderfully calming. Antonello plays the final Allegretto Graziosowith all the graceful phrasing that anyone could ask for and the piece ends with a satisfying finale.

The Sonata in D Minor is the pièce de resistance on this CD. It is Brahms in his most dramatic guise and his velvet tonal colorings can be deep crimson. I love the chromaticism in the first movement and the gorgeous double-stopping in the second. Brahms catches us all up in his musical web. The duo excites us with their dramatic interpretation of his exquisite melody. Violinist and pianist are equals here and at one point the piano has the melody while the violin plays a pizzicato accompaniment. The final movement of this sonata is prime beefsteak. Brahms crowns this sonata with a dramatic and incredibly melodic fourth movement packed with musical opulence. Antonello and Arnstein play its radiant finale with confident and spirited musicianship. Best of all, the Sonatensatz that ends this program takes up where the sonata leaves off and allows us to swim in another of Brahms’s deeply melodic pools. Antonello and Arnstein perform all of this music with animated and often exuberant playing. As with other Antonello recordings, the sound is clear and clean. There are numerous comparable recordings of these three Brahms sonatas. Anne-Sophie Mutter and Alexis Weissenberg play them at rather fast tempos on a 2003 EMI disc. Itzhak Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy made a memorable recording of them at a much slower pace in 1998 for Warner Classics. That same year Pinchas Zuckerman and Daniel Barenboim recorded their most individual interpretations for Deutsche Grammophon. Antonello and Arnstein’s CD has the best sound, but I will leave the choice of violinists and pianists to the individual music lover. You might want more than one version of these works.

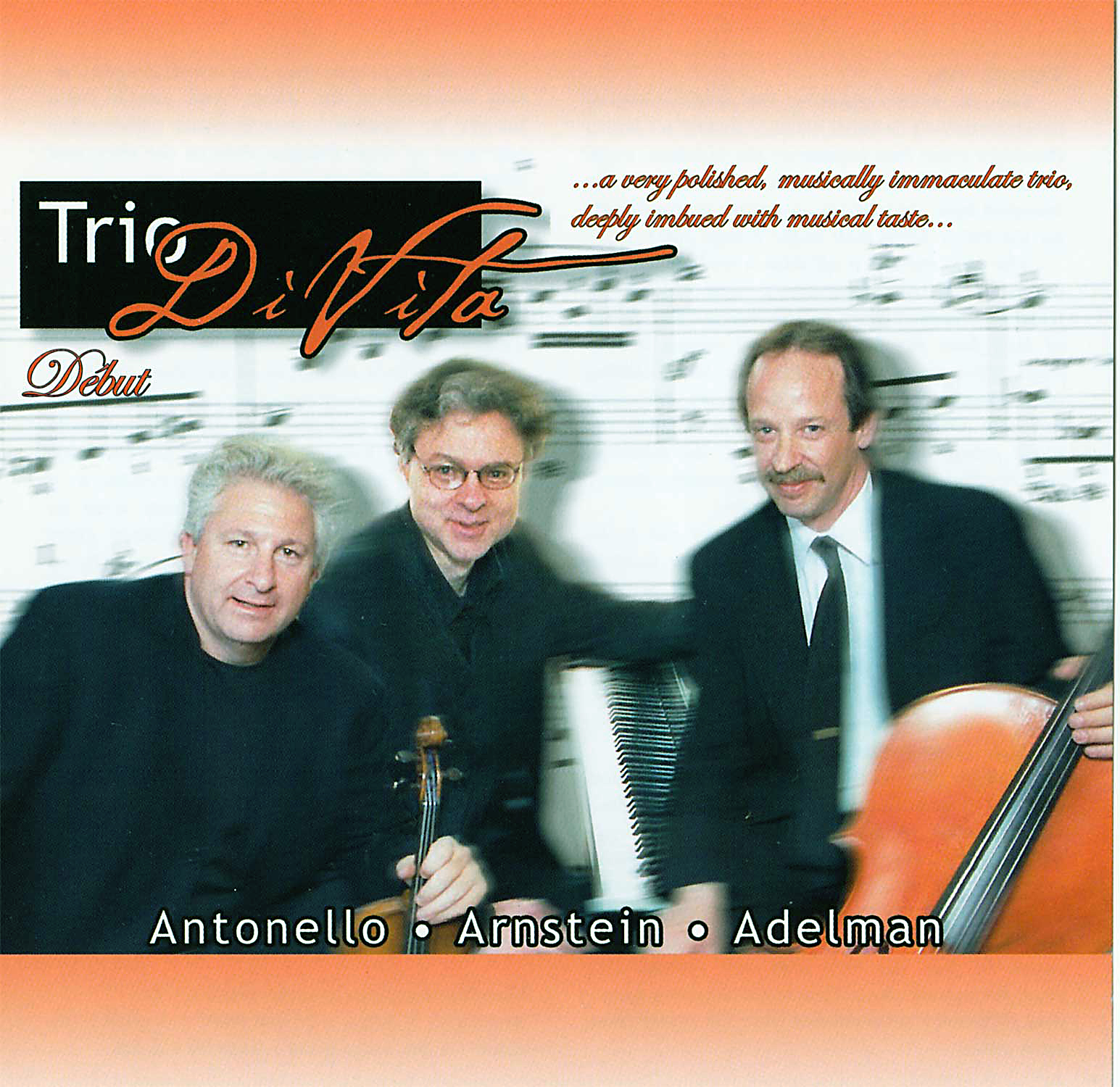

Robert McColley - Fanfare Magazine

TRIO DI VITA: DÉBUT • Michael Antonello, vn; Scott Adelman, vc; Peter Arnstein, pn. • MJA 00 (2 CDs: 102:28)

BEETHOVEN Trio No. 1 in E♭, op. 1/1. MENDELSSOHN Trio No. 1 in d, op 49. BRAHMS Trio No. 1 in B, op. 8. ARNSTEIN Trio yazzico nostalgico. Scottish Fantasy

Each member of Trio di Vita is a highly accomplished professional musician, though violinist Michael Antonello also runs a financial business and cellist Scott Adelman flies passenger jets. Antonello and Peter Arnstein have been playing as a duet since 1995 and have released three discs, all favorably reviewed in Fanfare; Adelman joined them in 2003 for a series of concerts during the Edinburgh Festival. This release commemorates those concerts. The major works on the program are from the top drawer of the ample literature for the piano/violin/cello combination, and Trio di Vita plays all of them with energetic relish, deep conviction, and secure technique. These clearly recorded performances are fully competitive with those of “big name“ ensembles. Trio di Vita is perhaps most persuasive in the early Brahms Trio, played—as is almost always the case these days—in the revision of 1890.

The two pieces by Peter Arnstein, composed expressly for the Edinburgh concerts, reflect his fascination with various musical styles, and his tendency to express his affection for them in whimsical ways. Each is about eight minutes long. The Scottish Fantasy is in one movement, whereas the Triojazzico nostalgico is in three. They are quirkily named “Moderato sentimentale,“ “Allegro awk-wardito,“ and “Presto scurrilissimo.“

There is no jazz in the first of these, an essay in early 20th-century salon music. Nor is the Allegro awkward for such proficient musicians, but it is stylistically far removed from its sentimental precursor, consisting chiefly in brief fragments from each of the instruments, ingeniously juxtaposed. Something jazz-like emerges in the Presto, a pleasant essay in the style of George Gershwin—with no scurrility that I can detect. The Scottish Fantasy is an altogether more serious piece, which successfully incorporates Scottish material. .

This article originally appeared in Issue 29:1 (Sept/Oct 2005) of Fanfare Magazine.

Daniel Morrison - Fanfare Magazine

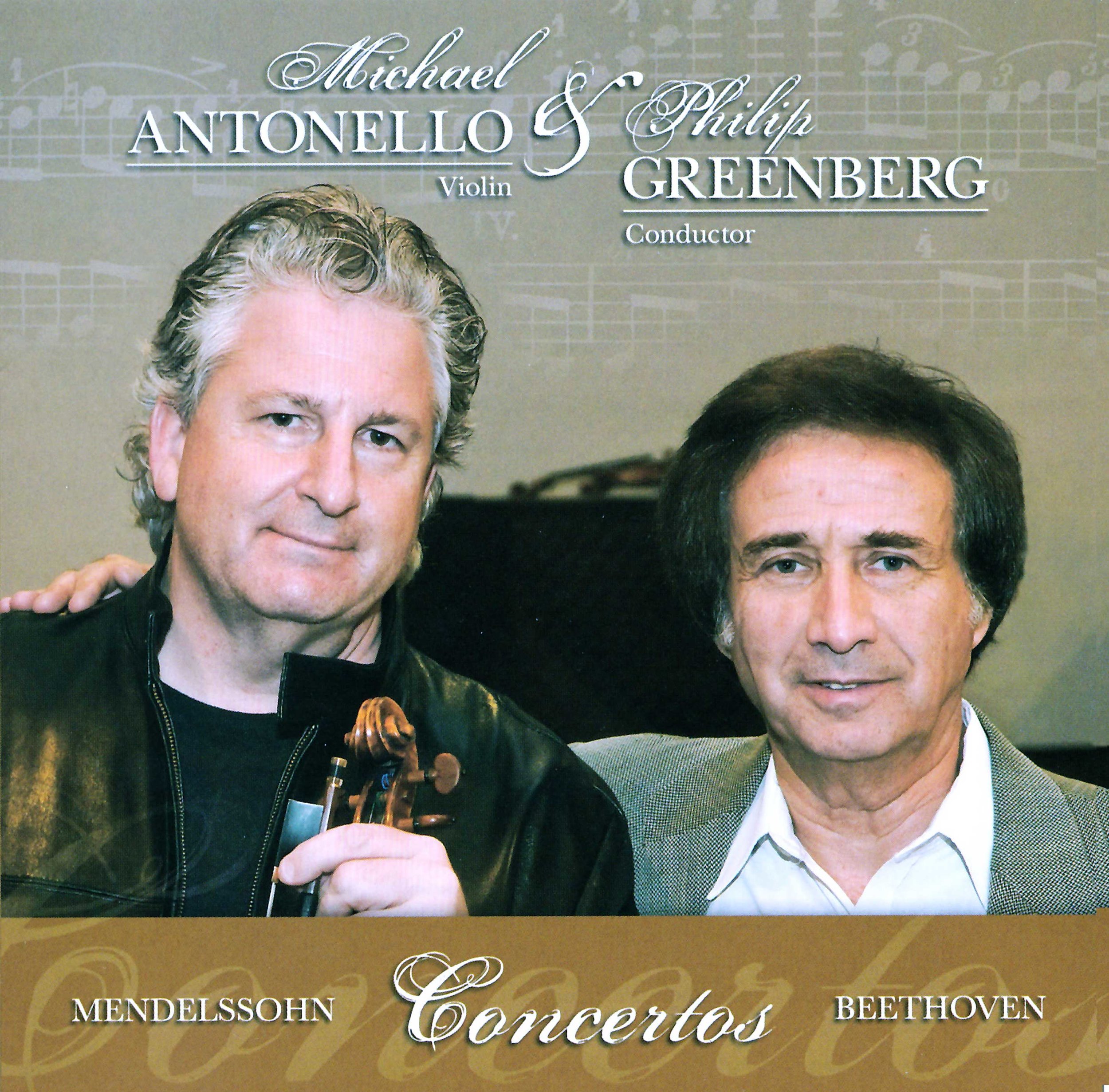

TCHAIKOVSKY Violin Concerto. GLAZUNOV Violin Concerto • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; Ukraine Natl SO • MJA (58:45)

Tchaikovsky has come up quite a bit in the estimation of sophisticated music lovers since my childhood in the mid 20th century, when he was still frequently denigrated by musical snobs as “too emotional.” (Imagine that—emotion in music!) Today few would deny his greatness as a composer or side with the 19th-century Vienna critic Eduard Hanslick, whose scurrilous review of the Violin Concerto, replete with Germanic anti-Slav racism, is cited in the notes for this recording. This concerto has gained a secure place among the masterpieces of its genre and has been recorded by generations of great violinists, so any new recording needs to justify itself through sheer excellence or a distinctive and persuasive interpretation.

My response to Michael Antonello’s rendition is mixed. In the notes for this recording, he remarks that he had the opportunity to work with the violinist Adam Han-Gorski, who “had many interesting ideas about bowings, fingerings, and interpretation.” (Han-Gorski was a student of Heifetz, who in turn was a student of Leopold Auer, the original dedicatee of the concerto, but on the other hand Auer initially refused to play the piece and eventually made a revised version of it for his own use, so the supposed connection to the source is a bit tenuous.) The only deviation from standard practice Antonello cites in detail was actually his own idea and comes at the soloist’s initial entrance (he plays three notes slurred, then five slurred, then five again, instead of the customary two, three, and eight). After a rather plodding orchestral introduction, the violinist’s entrance is promising. In the predominantly lyrical writing early in the movement, the large and opulent tone of Antonello’s “Ex-Rochester” Stradivarius, almost viola-like at the lower end, pleases the ear, and his weighty and leisurely approach and pronounced rubato are interesting. He handles the more rapid and technically demanding passages in the movement competently, although without the degree of fluency and security that many other performers deliver, and he sometimes seems hard-pressed, despite approaching these segments at a more deliberate tempo than usual. These passages can seem dogged and labored rather than brilliant. The dissonant double-stops beginning at 8:48 in this movement are unpleasantly grating, but Antonello plays well, if very deliberately, in the cadenza. I’m somewhat disappointed by the slow movement, where much of the time one note seems to follow another without much shaping or lyrical flow. I do, however, like the prominence of the winds in their dialogues with the soloist. The rapid passagework of the finale is again something of a struggle for Antonello, and the results are less pleasurable than in many other recordings, as his sumptuous tone deteriorates under pressure. Under Philip Greenberg, the Ukrainian orchestra plays capably and exposes much instrumental detail, but orchestral tutti seem rather foursquare and static. The sound of the recording is good, open and spacious, with well-defined positioning of the instruments, but dynamic range seems somewhat limited.

The Glazunov concerto, although more modest in scale, is a work of great beauty and deserves to be taken seriously as a contribution to the genre. The achingly poignant melody that opens the second movement never fails to move me deeply. I again have mixed feelings about Antonello’s performance. Once again his rich-toned playing is enjoyable, although in this case rather placid, in the predominantly lyrical writing of the first two movements, and the detailed support provided by the orchestra is also welcome. Enjoyment diminishes in the final movement, where the soloist’s technical limitations are again in evidence. He copes with the technical challenges, but one often has the sense that he is barely making it, with small imprecisions and tone that loses its allure under pressure.

For me these are frustrating performances, since pleasurable moments alternate repeatedly with those that are not so, and my judgment is that there too many shortcomings to permit a recommendation. However, those who have admired Antonello’s prior recordings, which I have not heard but which have been favorably received in Fanfare, should not be deterred from giving this one a try. In both works I would rather enjoy the effortless virtuosity and silken eloquence of Nathan Milstein, or the fervent expressivity and tonal opulence of David Oistrakh, despite Antonello’s edge in sound quality over their elderly recordings. For a coupling of these two concertos, in recordings of more recent vintage, I can recommend Maxim Vengerov with Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic on Teldec, where technical proficiency and interpretive refinement combine to produce a thoroughly satisfying result. Gil Shaham also has contributed excellent performances of these works on separate DG discs.

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:3 (Jan/Feb 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.

David K. Nelson - Fanfare Magazine

SALUT D'AMOUR • Michael Antonello (vn); Peter Amstein (pn) • MJA (72:17) Available for $13 from: MJA Productions, c/o Arnstein, 804 W. Green St., Champaign, IL 61820

ELGAR Salut d'Amour. VITALI (arr. Chartier, Auer) Chaconne. BRAHMS Violin Sonata No. 1. GERSHWIN (arr. Heifetz, Arnstein) Porgy and Bess: Bess, You Is My Woman Now; It Ain't Necessarily So. PROKOFIEV (arr. Heifetz) Love for Three Oranges: March. KREISLER Aucassin and Nicolette. DVOŘÁK-KREISLER Slavonic Fantasy. ARNSTEIN Grasshopper Suite. RACHMANINOV Vocalise. NOVÁČEK (arr. Arnstein) Moto Perpetuo

Michael J. Antonello is a prosperous life-insurance agent from the Twin Cities, and MJA is his record label. This is the third Antonello/Arnstein CD that I have reviewed; two called Stradivarius & Steinway are reviewed in Fanfare 16:1 and 16:5. Perhaps I am by nature charitable, and unlike some colleagues I have no objection to reviewing vanity press labels, but I do not believe I am cutting Antonello any slack when I write that his recordings are unfailingly musical and really nicely (not spectacularly, not perfectly: nicely) played. I play them now and then for my own pleasure, which surely says something, and I've reviewed far inferior playing on commercial labels from supposed, or at least self-proclaimed, "soloists."

Understand that selling is what he does now, but he trained at Curtis and Indiana, studying under Franco Gulli among others, and has been a first violinist of a fine orchestra and concertmaster of a good one. His playing is of that professional level: His vibrato has no wobble, his tempos are concert tempos, but for an odd pause or two in the Moto Perpetuo there is no awkwardness to his phrasing, no stiffness in his bowing or left-hand facility, and while he indulges in portamento I don't sense it's used as a technical crutch. He does not have the technique of, say, Milstein in Nováček or Vitali, and now and then the awkward passages and double stops in Brahms throw some vinegar in Antonello's tone; so this cannot be compared in overall polish to the better commercial recordings, but this is fluent, cleanly articulated, and warmly spirited playing of no little accomplishment.

Arnstein is a proficient professional, a composer, pianist, and harpsichordist, also based in the Twin Cities. His semi-improvised improvements to published accompaniments, prone to being antic, made the first two CDs first-rate party records (things he did not do on a recital CD with his violinist wife Pam; Fanfare 19:5). Nothing here is quite as zanily boisterous as some things on those prior CDs, nor did Heifetz's accompaniments to the Gershwin pieces need Arnstein's distracting ministrations. That, the greater emphasis on violin virtuosity on this disc, and the presence of a major work, the Brahms Sonata in G, perhaps unwisely invite direct comparison with commercial recordings, where of course it is going to be found wanting in some particulars, focusing more attention on the violin playing, which again is graceful (Antonello is at his most persuasive in Kreisler and in cantabile pieces), expressive, and animated, but not really sparkling. We also have Arnstein's own composition, as wacky and agitated as one would expect from the source and the title, and worth mining for recital encores. The notes mention that Antonello and Arnstein toured this program in Scotland, so evidently Antonello is partly back in harness. The sound is smoother than for the prior CDs. In sum, not perhaps as charming as its predecessor releases but by no means unworthy of your attention.

This article originally appeared in Issue 22:6 (July/Aug 1999) of Fanfare Magazine.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

VIVALDI The Four Seasons. PUCCINI (arr. Arnstein) Opera Medley. BACH Partita No. 2 for Unaccompanied Violin: Chaconne • Michael Antonello (vn); Peter Arnstein (pn); Richard Haglund, cond: Erato CO • MJA (69: 43)

This MJA recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons gives the listener a great deal of interesting information on the individual pieces. Each of the seasonal concertos is preceded by violinist Michael Antonello’s reading of the appropriate sonnet, possibly written by the composer. The poems are also published in the booklet that accompanies the disc. Vivaldi was one of the most accomplished virtuosos of his day. His operas were popular and he often led the accompaniment to them, playing violin pieces in the intermissions between the acts. For a man with serious asthma problems, he had a great deal of energy. Antonello, too, is a fine virtuoso who has had the stamina to maintain both a business and an artistic career. We are told that he intends to stop recording and we can only hope that he will change his mind. His is a talent that needs to be heard. With Vivaldi’s “Spring” Concerto in E Major we see the season as it comes out of the desolation of winter. The birds fly overhead and the flower buds begin to open as we hear the composer, also a priest, evokes the season of Easter and rebirth.

Summer in Vivaldi’s time must have brought the lassitude of unending hot weather. How joyously Italians of his day must have welcomed even the slightest cooling breeze. The Concerto in G Minor shows us both the heat and a storm that brought both cool air and the danger of lightening. In the F-Major “Autumn” Concerto Antonello attacks the beginning section with a great deal of energy. He continues with the speed and precision of one who knows this piece from the inside out. He and conductor Haglund draw out the musical tension to eventually resolve it into a rousing melodic Finale. The final piece of The Four Seasons is the F-Minor Concerto dedicated to winter. Its discordant description of the season’s winds is palpable as it indicates bone-chilling cold. Eventually Vivaldi moves his listeners indoors and allows them to sit by the fire, but not before we understand his picture of snow and ice.

There are innumerable comparable recordings of this Vivaldi work. Joshua Bell is both soloist and conductor on a 2008 Sony Classics disc that is technically well done but somewhat lacking in emotional content. Sarah Chang plays with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra on a 2007 Warner Classics recording. Since the orchestra plays with no conductor Chang is in charge, and she plays a thoroughly arranged version of the concertos that is very much her own. One of the newer discs is Anne Akiko Meyers’s rendition with the English Chamber Orchestra on Entertainment One. Her virtuosity is unchallenged, but the result is not as exciting as I would like.

Listening to Antonello play the singers’ lines in the Puccini medley, it’s evident that he understands opera well enough to know exactly how great singers handle that composer’s music. His performance on the violin has the same graceful phrasing that we hear on recordings of Domingo and Pavarotti. Antonello’s violin sings with radiant tone colors. His low notes are especially warm and delectable in the final moments of the arias from La bohème. He adds a bit of embellishment to “O mio babbino caro” that will make sopranos jealous and his rendition makes the jaded opera lover see the aria in a new light. The finale on this recording is the Bach Chaconne. Antonello also has a very fine recording solely of Bach that includes three of his concertos. He knows how to play Bach and proves it again here.

David K. Nelson - Fanfare Magazine

STRADIVARIUS AND STEINWAY • Michael J. Antonello, violin; Peter Arnstein, piano. • MJA PRODUCTIONS 000 [DDD?]; 57:27

KREISLER Schön rosmarin. Liebesleid. Liebesfreud. Praeludium and Allegro “in the Style of Pugnani.“ Tambourin chinois. MONTI Csardas. LECLAIR Sonata in D for Violin and Piano. SAINT-SAËNS Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, op. 28. FOSTER (arr. Kalellis) Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair. MASSENET (arr. Marsick) Thai's: Meditation.

Mr. Antonello sells life insurance in Minneapolis, but he's no Walter Mitty on the fiddle. On the contrary, he's a Curtis and Indiana University-trained violinist who studied under Franco Gulli, and who served as concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony and as a member of the Minnesota Orchestra. Now, joining even the best orchestra's string section means exploiting a technique honed on solo repertoire so as to be able to reproduce the standard repertoire, in endless repetition, with the fewest possible errors, and the least possible individuality. To say that it generates unhappiness and dissatisfaction in the troops it to put it mildly. Antonello has said to hell with it, keeps his chops in shape, and can show these tangible benefits: he's playing on his 1736 Strad, is recording on his own label, and is accompanied by an excellent pianist and composer, also Minneapolis-based, who studied with Robert Goldsand, and who has improvised here a marvelous accompaniment to the very familiar Leclair Sonata. Best of all, from the standpoint of a former member of the tutti, Antonello can use rubato to his heart's content, and can play at any tempo he pleases. Freedom! Antonello is a poetic player (Charles Ives and Wallace Stevens certainly proved that insurance and artistic impulses needn't be incompatible), at his most persuasive when he can wrap his warm, rich tone around a Kreisler piece. Liebesleid is particularly wistful and tender. He and Arnstein provide some novel readings of the rhythms in the Saint-Saëns, and Arnstein cleverly fills in some gaps in the piano part. Antonello's dexterity is fully professional, and often quite admirable, but in moments of highest technical stress the tone suffers: he's working hard, and isn't tossing off the difficulties like great soloists can. For all its rough edges it is a propulsive rendition. Now and then a sour note or blurred passage mars the Leclair, but I was enchanted by Arnstein's ornate, new accompaniment. The packaging of this “private label“ recording is handsome enough, but nothing's said about the origin or background of the violin, and I was not cheered by such unfortunate typos as ' 'Praedudium and Allegro. “ The sound is a resonant church acoustic; the violin is recorded very brightly.

This article originally appeared in Issue 16:1 (Sept/Oct 1992) of Fanfare Magazine.

David K. Nelson - Fanfare Magazine

STRADIVARIUS AND STEINWAY II • Michael J. Antonello, violin; Peter Arnstein, piano. • MJA PRODUCTIONS 7192 [DDD?]; 63:43.

KREISLER La Gitana. Rondino on a Theme by Beethoven. Caprice viennois, op. 2. BACH-ARNSTEIN Suite No. 3 in C for Solo Cello, BWV 1009: Bourée. MOZART (arr. Kreisler) Rondo. SARASATE Ziguenerweisen, op. 20. HANDEL (arr. Arnstein) Sonata No. 3 in F for Violin and Piano, op. 1, no. 12. SAINT-SAËNS Danse macabre, op. 40 (arr. Arnstein). The Swan. BOROWSKI Adoration. GRANADOS (arr. Kreisler) Spanish Dance No. S in E Minor. BRANDL (arr. Kreisler) The Old Refrain.

Antonello is a life insurance agent from Minneapolis, but previously was a concertmaster at Grand Rapids and section member in the Minneapolis Orchestra. Arnstein is a professional pianist, harpsichordist, and composer, also Minneapolis-based. For more background on these artists, see my review of their first CD (Fanfare 16:1, p. 430). Except for the most taxing portions, where execution can get a bit rough, difficult works like Zigeuenerweisen, the “Haffner“ Serenade “Rondo,“ and Caprice viennois testify to the durability of Antonello's fine training at Curtis and Indiana. He excels in lyrical “salon“ pieces, and I doubt if you'll hear a more impassioned account of “Adoration, ' ' a popular parlor work of fifty years ago. Newer works, like Arnstein's Godowsky-like rewrite of Danse macabre, present a few more difficulties.

Arnstein's tinkering with the piano parts goes beyond what he did in the first release. Available gaps are filled with rapid notes and double-dotted passages, in the manner of the French Baroque, as if the piano had the harpsichord's lack of sustain. But Arnstein admits that recording on the “Horowitz“ Steinway (during its 1992 tour of the country) is his major inspiration here. During the Bach Bourée and the last movement of the Handel Sonata, he outraces Antonello, flying up and down the keyboard with rapid scales, flourishes of thick-textured chords, and a variety of other virtuoso devices that call Horowitz's own arrangements to mind. Meanwhile, Antonello plays his parts absolutely “straight.“ The effect is like standing outside of two practice rooms at a music school. In the third movement of the Handel, Arnstein throws harmonic caution to the winds, with a zany mix of pure Handel and Scriabin. Whatever MJA's commercial intentions here (there's no bar code or copyright notice), as a party record the truly inspired vandalism on Bach and Handel will see much use at my house.

Unfortunately the sound is steely hard, with annoyingly electronic reverberation, lending a raspiness to Antonello's Strad and accentuating intonation flaws. I enjoyed the CD, but then I may be one of the few whose tastes run both to “Adoration“ and musical mayhem.

This article originally appeared in Issue 16:5 (May/June 1993) of Fanfare Magazine.

Robert Maxham - Fanfare Magazine

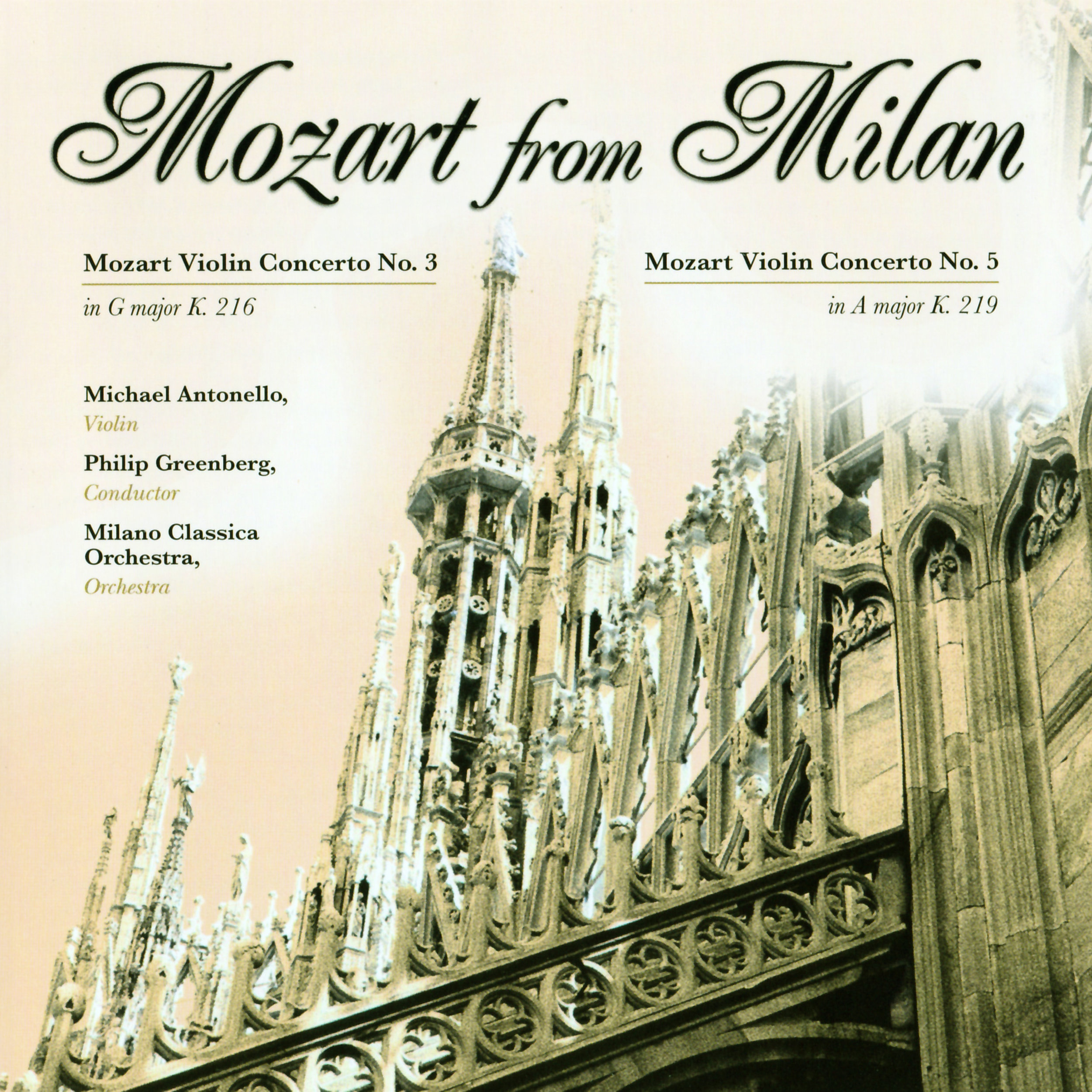

MOZART Violin Concertos: No. 3 in G; No. 5 in A, “Turkish” • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; Milano Classica O • MJA (56:44)

Peter Arnstein’s notes to Michael Antonello’s readings of Mozart’s Third and Fifth Violin Concertos engage in fascinating speculation about why young Wolfgang virtually abandoned the violin. Still, exiting the field, he left behind at least three concerted masterpieces (not to mention the Sinfonia Concertante or the sonatas he’d continue for a time to produce); Michael Antonello offers two of the concertos in readings to which he’s obviously devoted as much careful attention as Arnstein has to the notes.

In Mozart’s Third Concerto, the small Milano Classico Orchestra of 21 members plays enthusiastically in the first movement; Antonello, drawing upon both the strength and the sweetness of his 1720 Rochester Stradivari, gives an account of the solo part that combines the same two qualities in a similar measure—he approaches at some times the lively simplicity of Arthur Grumiaux and at others the energetic strength of Isaac Stern (though he’s not so straightforward, nor so smoothly virtuosic, as Stern in Sam Franco’s cadenza). Heightening the sense of the unexpected upon which Arnstein remarks in the notes, he supplements the text with ornamental ideas of his own. He and the orchestra give a gracefully flowing account of the second movement, marked by especially subtle expressivity in the middle section (but also by what sounds like occasional stiffness of his right-arm in passages involving string crossings). In the finale, the lyrical episodes glow in the light he shines on them. If the central section sounds less cocky than usual, that may be the result of Antonello’s generally melodic approach.

The violin’s slow entry in the Fifth Concerto’s first movement has become so well known as no longer to offer much of a surprise; Antonello graces it with individual portamentos that might offend purists but should delight an almost equal number of other listeners. To the movement proper he brings elegance and suavity mixed in similar proportions to those in his reading of the first movement of the Third Concerto (but also with occasional roughness in across-the-string bowings). His commanding tonal warmth and musical insight even relieve Joachim’s rather prolix cadenza of the tediousness some listeners unsympathetic to the idiom might otherwise experience. That assurance carries over to the slow movement as well as to the minuet-like first theme of the rondo finale; but he plays the signature exotic episodes with irresistibly jaunty piquancy; there and in the transitions between thematic materials, his deeply conceived reading lends the movement a special cogency.

The recorded sound throughout sports the somewhat anomalous combination of occasional edge with occasional dullness—all the time keeping the spotlight firmly fixed center stage on the soloist. Those who prefer personalized Mozart on modern instruments with modestly reduced orchestral forces should especially appreciate Antonello’s richly characterized performances, though those in search of perfection may not be inclined to forgive the strenuousness he occasionally exhibits (these concertos have widely been recognized as holding no prisoners). Recommended most strongly to those who have enjoyed Antonello’s thoughtful readings in the past.

This article originally appeared in Issue 33:6 (July/Aug 2010) of Fanfare Magazine.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

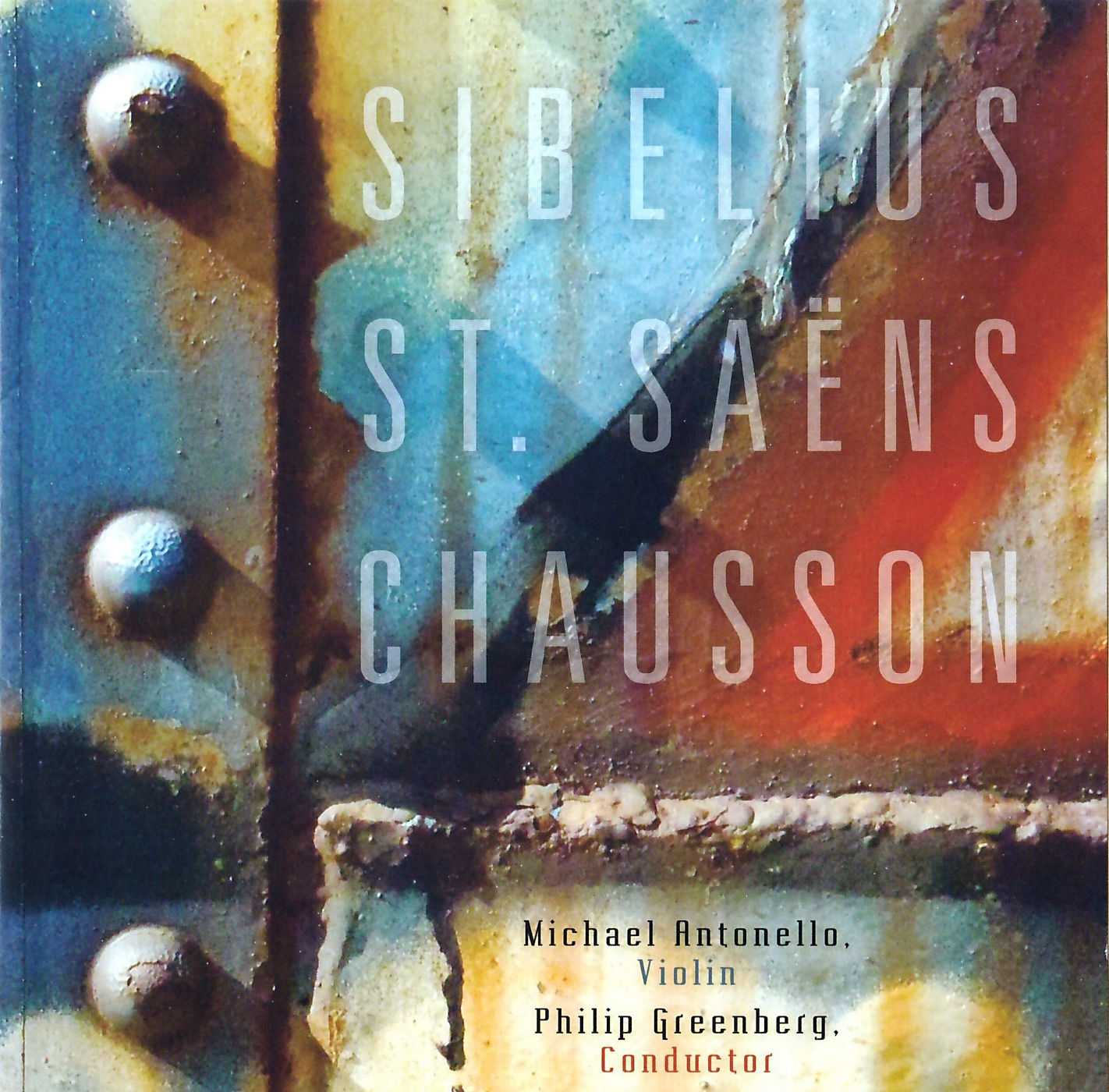

SIBELIUS Violin Concerto. SAINT-SAENS Violin Concerto No. 3. CHAUSSON Poème • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; Ukraine Natl SO • MJA PRODUCTIONS (79: 18)

Violinist Michael Antonello has with three well-known pieces jumped into competition with the greatest virtuosos on record. First of all, he deserves credit for daring to challenge lions in their den.

His first selection is the formidable violin concerto by Jean Sibelius. Choosing this concerto puts Antonello in direct competition with legendary violinists of the past, such as Jascha Heifetz and today’s top-selling virtuosos including: Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Anne-Sophie Mutter, and Hilary Hahn. Performing on his newly obtained 1742 Guarneri del Gesù, Antonello proves he can play with the best and earn a place at their table. He imbues his performance with considerably more emotion than Heifetz or Hahn. His first and last movements are slower and more expressively played than Mutter’s. He is not perfect all the time, but the sweetness of his tone, his solid ability to trill, and his open sincerity impress this listener. In the booklet Antonello says that the tone of the Guarneri is not as exquisitely beautiful as the Stradivarius on which he had previously performed, but less bow pressure is needed to produce its tone. In practice, the Guarneri lets him play with an even better technique and any difference in tone is imperceptible.

The third concerto by Camille Saint-Saens, the best-known of that composer’s works for violin, is tremendously demanding, as are his other pieces for solo instrument, and it hints at the neoclassicism that we will see with the next generation of composers. Antonello performs this dynamic concerto with precision and considerably more elegance than Cho-Liang Lin or Gil Shaham. Antonello never phones in his performance; he is present and contending for top honors with every single note. His contagious enthusiasm is the reason his interpretation surpasses that of Itzhak Perlman.

As for the Poème by Ernest Chausson, it is a great shame that we do not have more compositions from this composer. His output was not great and, unfortunately, he died in a cycling accident at a relatively early age. He studied with Massenet, whose influence can often be detected in the younger man’s compositions. Poème is just the right type of composition for Antonello’s talent; it takes instinct and expression of emotion. That is what he does best, and he does it without pulling the score out of shape. In this case he competes with Joshua Bell, who has a well-played recording from 1992 on London/Decca. Unfortunately, the sound on the older disc is seriously wanting. Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg has also recorded it, but her performance is marred by her tendency to exaggerate some aspects of the piece.

On this disc the soloist is well out in front of the orchestra in crystal-clear sound. Antonello and conductor Philip Greenberg have made a fine recording that lovers of violin music can enjoy for many years to come.

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:4 (Mar/Apr 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare Magazine

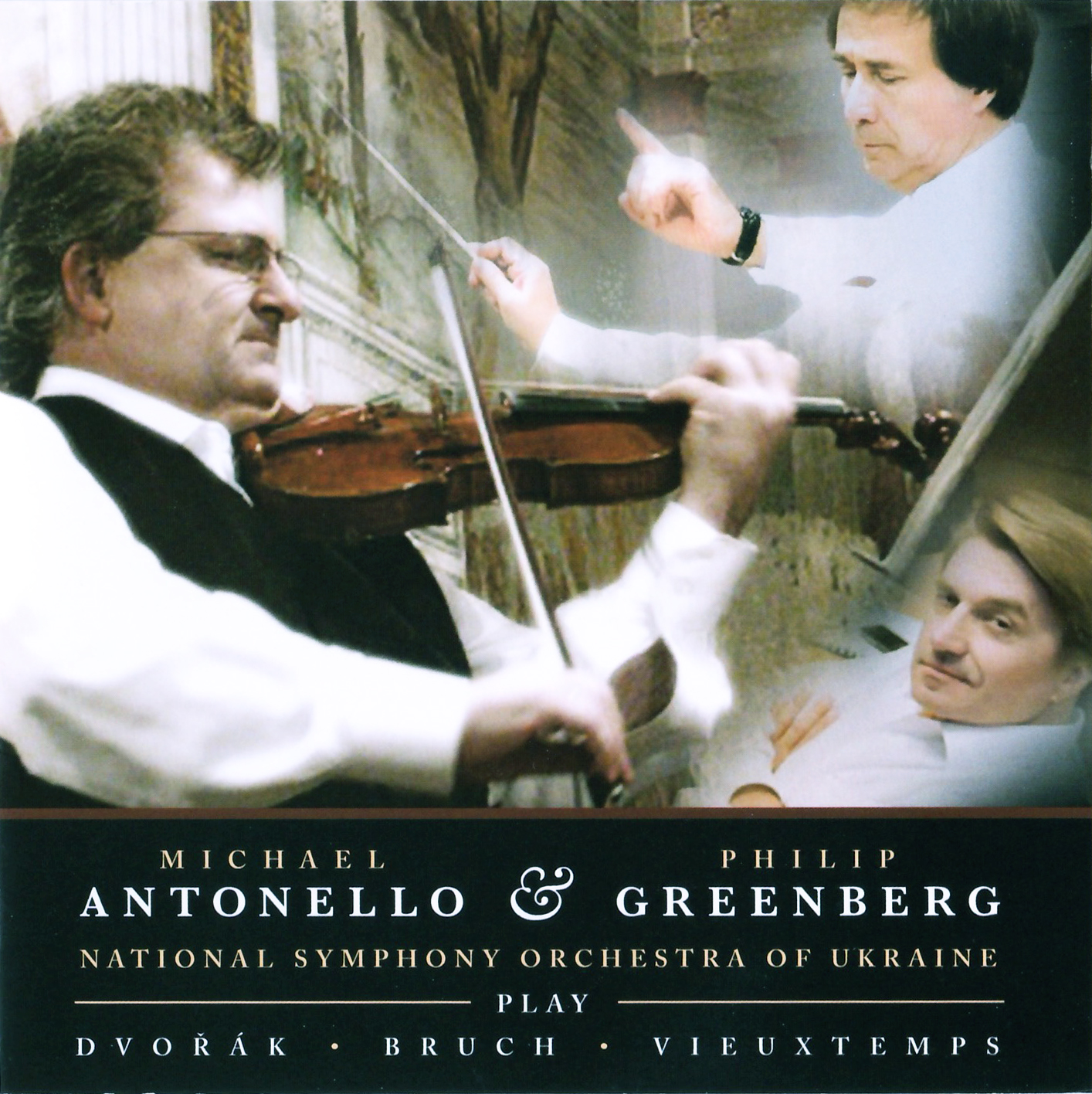

DVOŘÁK Violin Concerto. BRUCH Scottish Fantasy. VIEUXTEMPS Violin Concerto No. 5 • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; National SO of Ukraine • MJA PRODUCTIONS (2CDs: 81:02)

Antonín Dvořák loved the indigenous music of his Czech homeland and liked to use it in his compositions. His use of folk tunes is what makes his compositions distinctive. He did not play the violin professionally, however, and for that reason his concerto is difficult to play smoothly. He originally wrote it for the famous Joseph Joachim, who never performed it. Joachim was diplomatic and said he was editing the solo part, but it was finally premiered in Prague in 1883 by František Ondříček (1857-1922) who also played it in Vienna and London. Michael Antonello solves some of the concerto’s problems by slowing down the first and third movements while playing the second movement slightly faster. It works too, although it makes the first section sound somewhat less percussive. There is a sweetness to Antonello’s playing and he gives a very lyrical reading of this score. The composer’s great-grandson, Josef Suk III (1929-2011) made one of the most interesting recordings of the work. His well-crafted, workman-like rendition of the Dvořák concerto with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Václav Neumann was recorded some years ago. Since it was not released when it was made, it was remastered for its 2011 release on Supraphon. Itzhak Perlman, Daniel Barenboim, and the London Philharmonic play it with more fireworks on EMI, but some of the playing in the third movement lacks clarity.

Max Bruch, who was the conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic, wrote his Scottish Fantasy in E♭-Major on the continent during the winter of 1879-1880. He dedicated it to Pablo Sarasate, but Joseph Joachim played the 1881 premiere, and Bruch was not pleased with his interpretation. The piece’s four movements are based on tunes that embody the essence of Scottish culture. Rachel Barton Pine made a two-disc set of Scottish fantasies by various composers that includes her rather cool take on the Bruch. From it one can learn a great deal about Scotland and its music. It paints the central European Bruch in a different light.

Belgian violinist Henri Vieuxtemps composed his Violin Concerto No. 5 in 1861. It’s called The Gretry because its second movement is based on “Oú peut-on être mieux qu’au sein de sa famille?” (Where can we feel better than in our family?) from Gretry’s opera Lucille. Of Vieuxtemps’s seven concertos, the fifth is by far the most popular and it is played frequently. Jascha Heifetz recorded both the Scottish Fantasy and the Vieuxtemps Fifth Violin Concerto and both show his impeccable technique. His interpretations, however, were not known for their warmth. The Vieuxtemps, in particular, calls for warmth and lyricism, which Antonello brings us in huge measure. Here I am willing to give up some spectacular virtuosity for sincerity and emotional input. Most of the recordings compared with the new Antonello release are older and have less than state-of-the-art sound. The Pine recording, however, has sound that competes with the Antonello.

Dave Saemann - Fanfare Magazine

DVOŘÁK Violin Concerto. BRUCH Scottish Fantasy. VIEUXTEMPS Violin Concerto No. 5 • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; National SO of Ukraine • MJA PRODUCTIONS (2CDs: 81:02)

Most violinists we hear on recordings nowadays begin their careers either as prodigies or as pretty young faces on album covers. So, what happens to the violinist who starts his career with plenty of technique, then ripens as an artist in middle age when he becomes an exemplar of personality and maturity? Such is the case of Michael Antonello. Rather than travel as a full time virtuoso, he pursues a career in business, which undoubtedly accounts in part for the emotional strength and security of his violin playing. Like other violinists who play a Guarneri instrument, his sound is grittier and more individual than performers on Stradivarius violins, although Antonello has no trouble coaxing lyrical playing from his instrument. As a stylist, he reminds me somewhat of the late Ruggiero Ricci, although Ricci surpassed Antonello in sheer technique. In many respects, however, comparing Antonello to other violinists is quite beside the point. He is so much his own man that his interpretations are unlike anyone else’s. You hear him as a font of passion and wisdom. Indeed, it perhaps is typical of Antonello that, although he learned the Dvořák and Max Bruch works specifically for this recording, he sounds as if he has been playing them his whole life. At all times, you never are in doubt of Antonello’s poise, intelligence, and character. In this regard, he is greatly abetted by Philip Greenberg’s hand-in-glove accompaniments. In fact, I rarely have heard the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine perform as well as it does here. In sum, Antonello and Greenberg give us performances that may not always be the best available, but they certainly are the best of their type.

As the Dvořák Concerto opens, Antonello suggests the broad range of accents and colors of a folk instrument, while never losing the full texture of a concert violin. His passage work possesses a rare singing quality. At the start of the slow movement, Greenberg draws out an unusual blend of the winds with the soloist. Antonello’s handling of the main tune prefigures the world of Dvořák’s tone poems. His playing is intimate without ever descending to miniaturism. He opens the last movement with gorgeous tone colors. The tempo for the movement is just so, offering violinistic bravura without haste. The contrasting episode at the movement’s midpoint presents a cross between a late Beethoven string quartet and klezmer music. The coda features an unusual breadth of vision. Perhaps Itzhak Perlman and Tasmin Little provide more central recommendations for this concerto, and David Oistrakh’s 1949 recording is full of technical wizardry. Yet I would not be without Antonello’s version.

Antonello magnificently suggests the Scottish landscape’s melancholy at the start of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy. Greenberg and harpist Natalia Izmailova provide a gorgeous backdrop to Antonello’s bardic utterances. The violinist relishes the folk rhythms of the subsequent scherzo, and Greenberg’s response is appropriately unbuttoned. Flutist Larissa Plotnikova has a sprightly duet with Antonello. In the slow, third movement, Antonello conjures up a world of nostalgia, at a moment of high romanticism. As for the finale, a measured tempo allows for beautiful articulation by Izmailova. Antonello stops to smell the roses in his passagework—rarely has a violinist found so much music in the solo part. Antonello performs the Scottish Fantasy uncut. If you don’t mind a few nips and tucks, there are splendid recordings by Jascha Heifetz with Malcolm Sargent and by Alfredo Campoli with Adrian Boult. David Oistrakh with Jascha Horenstein is perhaps the best of the complete versions. Antonello’s recording, though, is highly distinctive.

Antonello’s individual sound is a great benefit in Henri Vieuxtemps’s Fifth Violin Concerto; one assumes that the composer’s playing was at least as striking. The orchestral part in Greenberg’s hands has rare clarity. The cadenza, far from being a stunt, possesses great probity. Antonello’s playing of the big tune before the ending is majestic and thrilling. Misha Keylin has recorded a fascinating cycle of all seven violin concertos by Vieuxtemps; his Fifth is excellent, but Antonello’s is just as good. The sound engineering throughout Antonello’s album is excellent, although I would have preferred slightly better definition for the orchestra. Michael Antonello’s splendid performances pose an important question: How many mature violinists, with much to contribute, are unable to make recordings? We are fortunate to have Antonello’s CDs. Will the public’s taste for youth and novelty ever allow many of Antonello’s peers to record? Don’t hold your breath.

Robert Maxham - Fanfare Magazine

DVOŘÁK Violin Concerto. BRUCH Scottish Fantasy. VIEUXTEMPS Violin Concerto No. 5 • Michael Antonello (vn); Philip Greenberg, cond; National SO of Ukraine • MJA PRODUCTIONS (2CDs: 81:02)

Violinist Michael Antonello, who has seemed for the last several years intent on recording the lion’s share of the standard repertoire for solo violin, for violin and orchestra, and for violin and piano, claims in his note to his set of concertos by Antonín Dvořák, Max Bruch, and Henri Vieuxtemps, that this will be his last effort in the genre. In Fanfare 34:3, I recommended his performances of violin concertos by Johannes Brahms and Bruch (No. 1) for their freshness; and since then, I’ve had the opportunity to trace his violinistic development (or recovery—since he had devoted a number of years to building his insurance business).