CD Gallery: click on the CD to read the booklet notes

MOSTLY SONATAS

Michael Antonello, violin, Peter Arnstein, piano

“As a violinist myself to sit less than three feet away from the most amazing performer I have ever seen was a true privilege. Michael Antonello plays with an intense energy and passion that has filled me with inspiration. His rendition of Fritz Kreisler‘s music blew me away with its technical brilliance and assurity. Pianist Peter Arnstein‘s performances were marked by a mixture of sensitivity and extreme emotion which was most apparent in his own composition, the quirky Trio Jazzico Nostalgico.”

ThreeWeeks Music Reviews 2003 A-D

The Edinburgh Festival Online - www.unlimitedmedia.cosuk/3weeks/reviews/revm- cad.html

“Antonello is a poetic player.”

Fanfare, September/October 1992

“...a violinist who can...elicit tears, laughter, and a standing ovation."

Grand Rapids Press, April 1994

“…not only is Antonello a joy to listen to, but also to watch, especially when he rises on tiptoes to reach the top notes.”

The Scotsman, (Edinburgh) August 30, 1995

“Antonello is accompanied by an excellent pianist... who has improvised here a marvelous accompaniment to the Leclair sonata...I was enchanted by Arnstein‘s ornate new accompaniment.”

Fanfare, September/October 1992

“The extraordinary physical composure of the Minneapolis-based Peter Arnstein on Friday night was in its way only matched by his formidable technical assurance, his sensitivity, his adroit choice of programme and his versatility.”

The Scotsman, (Edinburgh) August 20, 1985

“If Dr. Arnstein‘s fingers were nimble, his perceptions were crisper still, as he subsequently demonstrated in his harpsichord arrangement of a Vivaldi guitar concerto in D which accumulated an astonishing emotional intensity. Its release came in the pyro-technical brilliance of the concluding Allegro, with its firecracker vivacity and its whizzing scales.”

The Scotsman, Christopher Grier

Franck Sonata

Though a contemporary of Frederic Chopin, Robert Schumann and Franz Liszt, the brightest stars of the Romantic Era in Music, all of Franck’s greatest compositions appeared only after they had died, proving that a composer can be a success even if not a child prodigy. This sonata was written in 1886, the year that Liszt died. (He lived the longest of the three greats, Chopin having died in 1849, Schumann in 1856.) Franck was principally an organist, something one would never guess from his violin and piano sonata, which gushes with hot passion and heart-on-one’s-sleeve sentiment; it’s as if he were trying to prove he could write in a completely opposite way to the reserved formality of the organ. Franck was born a Belgian, but he took French citizenship; the sonata was written as a wedding gift for Eugene Ysäye, another Belgian, and himself a composer for the violin, and the dominant violinist of his age. Although he then premiered it and promoted it, he left no recordings of it behind. (Ysäye's historic recordings were made 1912-1914 and have been re-issued on CD.)

Brahms Sonata no. 3 in d minor

The storminess of the third sonata makes a distinct contrast to the lyrical, pastoral nature of the first two. It was begun in 1886, completed in 1888. Brahms had two trusted friends that he sent all his compositions to: the pianist and love of his life, Clara Schumann, and the violinist, Joseph Joachim. If Clara did not approve the composition, it was burned. With Joachim he worked closely on his violin concerto, and Brahms became so inspired with writing for violin, that three violin and piano sonatas soon followed the concerto. Joachim lived longer than either Brahms or Clara Schumann, leaving behind an early recording from 1906 of one of Brahms’ Hungarian dances. Brahms also left behind some fuzzy piano recordings from 1897 made on an Edison wax cylinder.

The thick, intense violin sound, (especially prominent in the second and fourth movements of the third sonata) that Brahms promoted in his violin concerto has become the standard for violin playing today, in fact sponsoring a modern revolt for lighter and smaller vibrato sound in the music of Bach and Mozart. Arnstein has a strong connection to this tradition, through his London teacher, Joan Davies, who studied with Ilona Eibenschutz, who studied with both Clara Schumann and with Brahms. Brahms and Joachim performed the premiere of the sonata in 1888 in Vienna.

Debussy Sonata for violin and piano

In 1915, Debussy’s publisher, Durand, announced Debussy’s grand project of six sonatas for various instruments. It was the middle of World War One, and when he completed the sonata, he signed himself Claude Debussy, French musician. Not only did he feel that his country and culture were under attack, as well as the death in war of many friends, but he himself was also in the midst of a battle with cancer. Of the six sonatas planned, he completed only three before he died: cello and piano; flute, violin, and harp; and this, his final composition, the violin and piano sonata. It was premiered on May 5, 1917. In a letter to a friend, he described it disparagingly as the product of a sick man in wartime.

But in spite of the physical pain and mental anguish the composer was suffering, his sonata is light, airy, full of magic, breathless moments, and incredible electricity and energy. The only hint that it is the product of a sick old man is the striking efficiency and compactness of the composition. It contains as much detail as an hour-long symphony by Mahler, yet lasts less than fifteen minutes.

About The Artists

Michael Antonello and Peter Arnstein recently released their first trio CD as part of Trio di Vita with cellist Scott Adelman, performing the Mendelssohn Trio in d minor, Beethoven’s first piano trio, the Brahms B Major trio, and two premieres by Peter Arnstein: Scottish Fantasy and Trio Jazzico Nostalgico. All the trios were performed to great acclaim at the Edinburgh Festival in 2003. This CD is part of a warm-up for the Edinburgh Festival in 2005, where Michael and Peter will be performing these pieces and more in two full programs (six concerts) from August 16th to August 23rd, at Reid Hall, St. Andrew’s and St. George’s Church, and Cramond Kirk.

Michael Antonello, a native of St. Paul, Minnesota, trained at The Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and in Bloomington, Indiana with violinist Franco Gulli. He was concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony in Michigan and the Rochester Symphony. He has also played with the Minnesota Orchestra and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. He and Peter have recorded three CDs which received rave reviews in Fanfare magazine. They have also performed at the Edinburgh Festival together. Michael is chairman of Wealth Management Advisors, which does life insurance and estate planning.

Peter Arnstein has won prizes in various international piano competitions. His first was the Watford Music Festival, in England, where judges heard twenty-two eleven-year-olds in a row play Knecht Ruprecht by Robert Schumann. The next day the judges probably had themselves committed to mental wards, but not before awarding first place to Peter. He has gone on to win prizes in many piano competitions, and in 1992 he won Gold Medal in all categories at the Roodepoort International Composition Competition for his composition: Orchestral Variations on a Theme by Mozart. Dr. Arnstein teaches piano and composition at the St. Paul Conservatory.

About The Violin

Antonio Stradivari, Cremona 1720 “Ex-Rochester”

A major inspiration for this CD and for the burst of concert activity that Michael has engaged in this year is the acquisition of his 1720 Stradivarius. He acquired the violin sight unseen, at the recommendation of James Warren of Kenneth Warren and Sons, a dealer in Chicago. The name Rochester derives from the town of Rochester in England, where it arrived sometime before 1823. It’s provenance can be traced from that time to the present. Because the Ex-Rochester has been possessed mainly by collectors, it is in remarkable condition. The Ex-Rochester was made during Stradivari’s seventy-sixth year. It is so exquisitely crafted that one is awed by the beauty and grace of the instrument. Hill, in his wonderful book about Stradivari, (1902, pages 66-67) marvels at his skill in 1720. This violin is one of the great fruits of his genius.

© 2005 MJA Productions

Sound Engineer: Tom Mudge

Editor: Cara-Mia Antonello

Recorded in Studio M at KSJN Minnesota Public Radio

PROGRAM

- Tempo di Minuetto - Fritz Kreisler 3:33

Sonata no. 3 in d minor, opus 108 - Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Allegro 7:47

- Adagio 4:25

- Un poco presto i con sentimento 2:58

- Presto agitato 5:55

- Chanson di Matin - Edward Elgar (1857-1934) 3:03

Sonata for violin and piano - Claude Debussy (1862-1918) - Allegro vivo 5:12

- Intermede 4:23

- Fantasque et leger 5:12

- Romance - Robert Schumann 3:43

Sonata for violin and piano - César Franck (1822-1890) - Allegretto ben Moderato 6:06

- Allegro — Quasi lento — Allegro 8:30

- Andante 7:09

- Allegretto poco mosso 6:11

BACH UNACCOMPANIED SONATAS AND PARTITAS

What if modes of artistic expression were arranged not by subject, such as music, drama, literature, painting, etc., but by the onstage lifestyle they imposed on the performer? What if one brought together all the lone performers who had nothing but an empty stage and a spotlight to do their thing? Then, all the following could be grouped under one category: Stand-up comedians, mimes, actors in one-man shows, solo a capella singers, and poets. Pianists would fit, but not piano music, which, as it has developed from Bach to composers such as Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Szymanowski, has come to imitate and resemble that of an orchestra, incorporating harmony, color, and melody. Into the hermetic image of such a lone figure onstage belong the solo works of Bach: three suites for violin, three partitas for violin, six suites for cello, and one suite for flute. Although the music contained in these works bears all the hallmarks of Bach's musical personality, sometimes including polyphony, the striking feature of these works is how alone the music makes the performer appear to the audience. If a Brandenburg concerto is like the field of riches one encounters at a summer arts festival such as Edinburgh's—where one can get one's cultural fix, morning, noon, and night, with a dazzling selection of drama, music, dance, literature, film, art, comedy, and more— a Bach instrumental solo is like a deserted Scottish isle, where one stands on the cliffs, blown about by the cold wind, too strong even for seagulls, observing the rocks and foggy surf down below, out of sight of human habitation or human existence or any life other than a few tough tufts of heather clinging to the rocks, utterly alone. Bach's music in this genre deals almost exclusively with melody; harmony is only implied, never blatant. To achieve such an incredible depth of expression using melody alone makes these works unique in the annals of music. It also makes them dense with musical expression; Johannes Brahms, who made a famous piano transcription of the Chaconne (from Partita No. 2) for left hand alone, wrote to Clara Schumann about the music: On one stave, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of ray mind.

Many composers of the past took pride in being proficient in writing for every type of instrumental and vocal combination. Yet solo works such as these are absent from the canon of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and most other major composers. The Belgian violinist Eugene Ÿsaye (1858-1931), who spent his performing life inspiring violin and piano works or violin concertos from other composers, produced six magnificent sonatas of his own for solo violin (and one for cello), all showing inspiration from Bach. The third begins with the opening to Bach's E major partita, and it turns into a mad fantasy on it, in fact titled Obsession. Each of his sonatas is dedicated to a different violinist, and fitted to their style of playing. The third sonata, titled Ballade, is perhaps the only piece in the entire literature which, in its ability to project extremes of passion, could be compared to Bach's Chaconne. The Chaconne and the E major Prelude are frequently performed by themselves, and both have benefited (or suffered) from being transcribed for other instruments. Busoni's transcription of the Chaconne for piano, is markedly inferior to the original, though Horowitz and others have performed it. On the other hand, Rachmaninoff's transcription of the E major Prelude is a wonderful piece, beginning in the style of Bach and ending in the style of Rachmaninoff (1873-1943), resulting in a vast and magical two-century metamorphosis, compacted and reduced to the space of a mere five minutes. The Ÿsaye works are the only ones which could be considered to have the depth of feeling and range of emotion of Bach's works. With the exception of the Prokofiev Sonata, the Paganini Caprices, and possibly Reger's third cello sonata, no other works in this medium have come remotely close to such lasting popularity. This is a partial list of instrumental solo music for which recordings are available:

Heinrich Biber (1644-1704): Passacaglia and Chaconne

Telemann (1681-1767): 12 Fantasias for violin

Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840): 24 Caprices, considered virtuoso show pieces

Max Reger (1873-1916): 3 suites for solo cello; a violin sonata

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962): Recitatif and Scherzo

Béla Bartok (1881-1945): solo violin sonata

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953): solo violin sonata

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) Sonata for violin

Henri Vieuxtemps (1820-1881): 6 pieces for violin

Astor Piazolla (1921-1992): 6 etudes for flute or violin

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998): one fugue for violin

Bach composed his solo violin works between 1703 and 1720. He worked briefly in Weimar with an older composer, Joahnn Westhoff, who published partitas for solo violin, showing Bach the possibilities for composing in this form. No one knows who, if anyone, performed these works publicly during Bach's lifetime. Bach himself was more than capable, having received far more training on the violin than on the organ or the harpsichord, even though he eventually became known as a virtuoso on those two keyboard instruments.

MICHAEL ANTONELLO, VIOLIN

Michael Antonello attended the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia as a student of Joseph Brodsky, followed by studies at Indiana University, where he worked with violinist Franco Gulli. He was also engaged as an orchestral and chamber musician at the Mostly Mozart Festival in New York. Following his studies, he was appointed concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony. In addition, he has served as concertmaster of the orchestras of the Aspen Festival and the Rochester Symphony Orchestra in Minnesota, and held temporary tenures with both the Minnesota Orchestra and the St, Paul Chamber Orchestra.

Mr. Antonello has recently been the featured soloist of the Erato Chamber Orchestra of Chicago, the Rochester Symphony, Milano Classica, the Romanian Philharmonic, and St. Petersburg's State Capella Orchestra. Antonello has also performed extensively in recital with pianist Peter Arnstein, including regular performances at the Edinburgh Festival. Together they have recorded seven CDs.

Mr. Antonello has recorded many violin concertos, including the Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch no. I and the Scottish Fantasy, Mozart no. 1, 3,1, & 5, Sibelius, Glazunov, Tchaikovsky, Vieuxtemps no. 5, Bach (The E major, a minor, and Double), Dvoràk, Saint-Saëns no. 3, Chausson's Poeme, and the Vivaldi 4 Seasons. He also recently finished recording all of Bach's works for solo violin.

In 2009 he co-founded the Southern Tuscany International Festival of Music, Literature, Food, and Wine.

Performing on his newly obtained 1742 Guarneri del Gesù, Antonello proves he can play with the best and earn a place at their table. He imbues his performances with considerably more emotion than Heifitz … the sweetness of his tone … and his open sincerity impress this listener … contending for top honors with every single note. His contagious enthusiasm is the reason his interpretation surpasses that of Itzhak Perlman … Poème is just the right hype of composition for Antonello's talent; it takes instinct and expression of emotion. That is what he does best, and he does it without pulling the score out of shape.

Maria Nockin - Fanfare, March/April, 2012, (review of Sibelius and Saint-Säens concertos, and Chausson's Poeme)

CARA MIA ANTONELLO

Cara Mia Antonello held the position of Principal Second Violin with The Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra from 1982-1997. Prior to her St. Louis tenure. Ms. Antonello spent five years with The Hague Philharmonic in The Netherlands, also as Principal of the second violin section. A native of St. Paul, Minnesota, Antonello studied with Dorothy DeLay at both the Juilliard School in. New York and the Aspen Music Festival. She also served as Concertmaster in festival orchestras conducted by Yehudi Menhuin and Aaron Copland, and is a grand prize winner of the prestigious WAMSO competition.

Ms. Antonello has been featured as a soloist with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, The Hague Philharmonic, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Saint Louis Philharmonic, Jacksonville Symphony, Nebraska Chamber Orchestra, and many other regional orchestras around the country.

Ms. Antonello's chamber music experience includes performing and touring throughout Europe with the Resident Quartet of The Hague Philharmonic and frequent string quartet performances on WQXR, New York. As a member of the Webster University faculty, she led the Webster Piano Trio in performances throughout the Midwest.

Her extensive teaching experience includes appointments at Washington University, St. Louis University, the St. Louis Symphony Music School. Webster University, and Southern Illinois University. Recently, Cara Mia has been on the jury of major violin competitions, including the prestigious Wteniawski competition in Poznan, Poland and the Sion-Valai competition in Switzerland. She currently maintains a private studio, coaching both chamber music and orchestral repertoire for auditioning candidates.

© 2012 MJA Productions

Producers: MJA Productions

Recording & Mastering: Ryan Albrecht, Senyah Sound

Editing: Cara Mia Antonello

Booklet Notes: Peter Arnstein

Graphic Design: Troy Savageau

Cover photo courtesy of Warren Adelson, Adelson Galleries, New York

NOTE FROM THE VIOLINIST:

This project was recorded in three different acoustic spaces from July 2011 to June 2012. I am grateful for the tireless work and commitment of my sister Cara Mia Antonello, she is a great violinist who spent countless hours listening to and editing these complicated works. I would also like to acknowledge our sound engineers Tom Mudge, and Ryan Albrecht of Senyah Sound who were dedicated to getting the best sound quality from each space.

The polyphonic genius and beauty of Bach's music manifests best within a very simple formula - play all of the notes with a beautiful sound, excellent intonation (pitch), and relentless steady rhythm. This is difficult to accomplish. The musical expression must be made within these restricted parameters, so that is the challenge. Sonata #1 and Sonata #3 were recorded at St. Paul's Church in Chicago. The 1st, 2nd, and 4th movements of the d Minor Partita were recorded at The Hemingway Museum in Oak Park Heights, Chicago and everything else was recorded at the Unitarian Church of Mahtomedi, MN. The best recording acoustic was St. Paul's Church, it is a classic rectangular space like most of the best halls in the world. The natural reverberation in the hall does not boomerang all the way back and on top of the violin, but rather a bubble is created in which the greatness of the del Gesu violin sound is evident. The wonderful acoustic helps the result in this challenging music.

PROGRAM

CD 1

Sonata No. 1, in G Minor, BWV 1001

I. Adagio

II. Fuga: Allegro

III. Siciliana

IV. Presto

Partita No. 1, in B Minor, BWV 1002

I. Allemanda/Double

II. Corrente/Double

III. Sarabande/Double

IV. Tempo di Borea/Double

Sonata No. 2, in A Minor, BWV 1003

I. Grave

II. Fuga

III. Andante

IV. Allegro

CD 2

Partita No. 2, in D Minor, BWV 1004

I. Allemanda

II. Corrente

III. Saraband

IV. Giga

V. Ciaccona

Sonata No. 3, in C Major, BWV 1005

I. Adagio

II. Fuga

III. Largo

IV. Allegro assai

Partita No. 3, in E Major, BWV 1006

I. Preludio

II. Loure

III. Gavotte en Rondeau

IV. Menuet I and II

V. Bourree

VI. Gigue

BACH VIOLIN CONCERTOS

Residing in Leipzig since 1723, in 1729 Bach became director of the Collegium Musicum, which had been founded by his colleague, Georg Phillip Telemann. At that time there was no such thing as a public concert. The Collegium Musicum was a private society started by university students who were active musically. They performed two-hour concerts twice weekly in a coffeehouse. Bach’s violin concertos were probably written for and performed at those concerts.

By the time Bach joined the Collegium Musicum, he had written a huge number of church cantatas, far more than would ever be needed for all the church services of the year. The Collegium Musicum thus represented an opportunity which he had never had before, of composing not out of obligation but for fun—even if he had to write out every orchestral part himself, which he did, unless he could corral one or another of his numerous sons to do the tedious job. The musicians who played his concertos and solo pieces for violin must have been of very high caliber. (Bach himself had plenty of instruction on the violin, but none on keyboard, even though he became famous as an organ and harpsichord virtuoso.) But what especially stands out in the concertos, especially the one in E Major, is the overwhelming sense of vitality and bubbly, unquenchable joyfulness. Just as Mozart’s operas were written for specific singers, Bach must have had particular violinists in mind, and he wrote to suit them. Both their names and the precise dates of the performances have been lost to history.

The time and effort he spent arranging the programs of the Collegium Musicum soon produced chastisement from his church employers; he was neglecting his teaching duties, sometimes abandoning them. But chamber music was so much more fun! And he got to escape, for awhile, the petty politics of his church committees, the bane of his existence.

However, he eventually brought everything he learned from his experiments with the Collegium Musicum into his church music, which he never ceased writing. His sons, also, felt it was felicitous to have their own experiences in the society on their resumes, when they applied later for music jobs. The Bach Double Concerto may first have been played by Bach’s two oldest sons; with Bach conducting from the harpsichord, this concerto would have been a true family affair. Unlike nineteenth-century concertos, which often depict a battle between soloist and orchestra, the Double is almost nothing but congeniality and cooperation between the parts, and one has to dig deeply to find a trace of sibling rivalry or other psychological dissonance described, if it is there at all. Woody Allen, however, heard enough intensity and strife in the melodic material itself to use the first movement in his movie, Hannah and her Sisters, introducing the first antagonist, the younger sister who would embark on an affair with the husband of her sister Hannah, upsetting the family's happy applecart, so to speak.

It was in the concerts of the Collegium Musicum that Bach became well-acquainted with the concertos of Antonio Vivaldi, undoubtedly including The Seasons, which are also recorded by Antonello. Much speculation has been written on the influence of Vivaldi on Bach, but there is no absolute proof of what this influence was. The speculation is based on a statement Bach made to one of his sons, that Vivaldi "taught him how to think musically.” This statement is intriguing, because all of Bach's music, even that from his formative years, is of very high quality, and second, the consensus of the ages has always been that Bach is the greater composer.

Christoff Wolff, professor at Harvard, has written a long essay on the subject, and on what Bach’s surprising statement might refer to. Bach spent his entire life studying and transcribing other composers’ music, with special study devoted to the Vivaldi violin concerti. Bach transcribed many of Vivaldi's violin concertos for solo harpsichord, so he could study them at his leisure. Bach recognized that the initial musical ideas which launch each of Vivaldi’s compositions drive the entire musical composition; everything grows and develops out of that first idea, and subsequent ideas gave birth to more ideas, and so forth and so on, and the listener can hear and feel that they only work in that order. In contrast, the musical ideas of vocal music unfold in the order that is determined by the words and story, and not the purely musical ideas. This particular type of writing, where the ideas generated are purely musical (as opposed to ideas from lyrics), made for a great change in the history of music. From then on, instrumental music, as opposed to vocal music, would dominate the musical scene and the composers who could best manipulate purely musical ideas would be considered the greats. This was a change from before, when the ability to put words to music (principally biblical texts) was considered the greatest test of talent. Bach felt that this change in musical history, which he desired to be part of, was set in motion by Vivaldi.

The Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068, came to be known as the Air on the G String after the movement was transposed and rearranged for solo violin with piano or orchestra. Bach composed his four Orchestral Suites when working for Prince Leopold in Köthen, who preferred secular works to the church music that Bach was accustomed to writing. The Air is the first piece of Bach’s ever to be recorded, in 1902 with cellist Aleksandr Verzhbilovich and an unknown pianist. Here it has been re-arranged by Peter Arnstein for solo violin and string orchestra, back to the original key of D Major

— Notes by Peter Arnstein

Michael Antonello, Violin

Before launching an international solo and recording career American-born violinist Michael Antonello attended the legendary Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia followed by studies at Indiana University. There he worked with concert violinist Franco Gulli until his appointment as concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony. He also has served as concertmaster of an orchestra at the famed Aspen Music Festival, and the Rochester Symphony Orchestra in Minnesota. He held a temporary tenure with both the Minnesota Orchestra and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. He has been featured as a soloist with the Erato Chamber Orchestra of Chicago, the Rochester Symphony, Chelsea Symphony, Milano Classica, Romanian Philharmonic, and St. Petersburg’s “State Capella Orchestra”. Antonello has also performed extensively in recital with pianist Peter Arnstein. They have seven CD's to their credit. These CDs include much of the standard Sonata Repertoire, as well as favorite violin showpieces. Mr. Antonello has recorded many violin concertos including the Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Brahms, and Bunch with conductor Philip Greenberg and the National Orchestra of the Ukraine. They have also recorded Mozart Concertos No. 3 and No. 5 with the Milano Classica Orchestra. He and conductor Richard Haglund have performed concerts in Chicago, St. Petersburg Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Moldova. Michael Antonello co-founded the Southern Tuscany International Festival of Music, Literature, Food, and Wine.

Michael Antonello plays on his 1742 Guarneri del Gesu, the Ex-Benno Rabinof made in the last four years of the maker’s life. There are only 25 violins from this period. They are rare and sought after for their power and unique tonal characteristics.

Richard Haglund, Music Director and Conductor

An engaging communicator of exceptional warmth and energy, conductor Richard A. Haglund is the founder and Music Director of the Erato Chamber Orchestra in Chicago. He is often in demand as a guest conductor, performer and clinician.

As a guest conductor, Maestro Haglund has lead professional ensembles in America and around the globe. These include the Camerata Chamber Orchestra in Cluj , Romania, the St. Petersburg Hermitage Orchestra in Russia, the Varna Philharmonic and Grabovo Chamber Orchestra in Bulgaria, Cappella Orchestra in St. Petersburg Russia and the National Chamber Orchestra of Moldova in Chisinau. Recently he was invited for a second appearance with the Bantul Philharmonic Orchestra in Romania. This summer he led performances in the Southern Tuscany Festival of Music in Italy. Haglund’s diverse experience includes Pops Conductor for the Greater Newburgh Symphony Orchestra's summer season, Assistant Conductor of the Woodstock Chamber Orchestra and the Bard Community Chorus. This past summer he conducted the Broadway reading preview of “Song of Solomon” in New York City.

A native of Minnesota, Maestro Haglund received his musical training on Percussion and Piano. Haglund holds a Bachelor of Music degree from the University of Minnesota and a Masters degree in Orchestral Conducting from Bard College Conservatory of Music where he studied with Harold Farberman and Leon Botstein. In addition to his conducting degree, he has studied composition with world-renowned composer Joan Tower at Bard Conservatory in New York.

Maestro Haglund has studied conducting throughout the world with numerous teachers, most notably Gustav Meier, Paul Vermel, Larry Rachleff, William Jones, Emil Aluas and Philip Greenberg. His previous appointments include Music Director and conductor of the Heartland Symphony (MN), Northeast Orchestra (MN), and Sangamon Valley Youth and Community Orchestra (IL). He served as assistant conductor of the Illinois Symphony Orchestra for several seasons and visited thousands of elementary students every year in his outreach activities.

Erato Chamber Orchestra

The Erato Chamber Orchestra is comprised of Chicago’s finest musicians who have a common affection for making and sharing music. The ensemble’s programs are devoted to both classical and contemporary repertoire that is not ordinarily played by large symphony orchestras. Their name is inspired by the Greek goddess Erato, who is the Muse of Lyric Poetry. The orchestra's style is characterized by a warm sound and virtuosic talent combined with an infectious enjoyment of the pleasure of making music.

Ruggero Allifranchini, Violin

Ruggero Allifranchini is the Associate Concertmaster of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and the Concertmaster of the Mostly Mozart festival orchestra in New York. He was born into a musical household in Milan, Italy and raised on a diverse musical diet, ranging from Beethoven to John Coltrane. He studied at the New School in Philadelphia with Jascha Brodsky and later at the Curtis Institute of Music, studying with Szymon Goldberg and chamber music with Felix Galimir. He was the recipient of the Diploma d’Onore from the Chigiana Academy in Siena, Italy. In 1989, he co-founded the Borromeo String Quartet, with which he played exclusively for eleven years.

As a chamber musician of diverse repertoire and styles, Allifranchini is a frequent guest artist of the Chamber Music Societies of Boston and Lincoln Center, as well as chamber music festivals in Seattle, Vancouver, and El Paso, among many others. He is the violinist of the trio Nobilis, with pianist and former SPCO Artistic Partner Stephen Prutsman and cellist Suren Bagratuni. Nobilis has performed chamber music as well as solos with orchestras in Europe, South America, and South Africa as well as North America.

Allifranchini plays on the “Fetzer” violin made by Antonio Stradivari in 1694, which is on loan to him from the Stradivari Society of Chicago.

© 2012 MJA Productions

Recorded at The Arts Center of Oak Park in the Lora Aborn Auditorium 200 N. Oak Park Avenue, IL 60302 December 5-7, 2011

Conductor: Richard Haglund

Producers: MJA Productions

Recording, Editing, & Mastering Engineer: Ryan Albrecht, Senyah Sound Music Producer & Editing: Cara Mia Antonello

Orchestra: Erato Chamber Orchestra

Booklet Notes: Peter Arnstein

Graphic Design: Troy Savageau

PROGRAM

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): Violin concerto in a minor, BWV 1041

Michael Antonello, Violin

Allegro moderato 4:02

Andante 6:12

Allegro assai 4:02

Violin Concerto in E Major, BWV 1042

Michael Antonello, Violin

Allegro 8:09

Adagio 5:55

Allegro assai 2:50

Concerto for 2 Violins, Strings & Continuo in D Minor, BWV 1043

Ruggero Allifranchini, Violin - Michael Antonello, Violin

Vivace 3:42

Largo ma non tanto 6:29

Allegro 4:57

Air on the G String (arr. Peter Arnstein) BWV 1068

Michael Antonello, Violin

Air from the Overture No. 3 in D Major, 6:19

Total running time 52:44

BRAHMS SONATAS

ANTONELLO / ARNSTEIN DUO

Violinist Michael Antonello and pianist/composer Peter Arnstein have performed together for more than 25 years. Their five CDs, Stradivarius and Steinway, Stradivarius and Steinway II, Salut d’Amour, Moslty Sonatas, Poeme and Back to Back have all received critical acclaim. They have also appeared three times at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, where Arnstein has also appeared several times as a solo pianist and harpsichordist. Besides frequent concerts in the Midwest, they have done two tours of Italy. In 2003, they went to Scotland as part of the piano trio, Trio di Vita, with cellist Scott Adelman, and released a trio CD of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Brahms, and two world premieres by Arnstein.

“Michael Antonello plays with an intense energy and passion that has filled me with inspiration … Pianist Peter Arnstein’s performances were marked by a mixture of sensitivity and extreme emotion.”

The Edinburgh Festival Online

“Antonello is accompanied by an excellent pianist who has improvised here a marvelous accompaniment to the Leclair sonata I was enchanted by Arnstein’s ornate new accompaniment.”

“Performing [the Sibelius violin concerto] on his newly obtained 1742 Guarneri del Gesù, Antonello proves he can play with the best and earn a place at their table.”

“Antonello performs this dynamic concerto [Saint-Saëns Concerto No. 3] with precision and considerably more elegance than Cho-Liang Lin or Gil Shaham. Antonello never phones in his performance; he is present and contending for top honors with every single note. His contagious enthusiasm is the reason his interpretation surpasses that of Itzhak Perlman.”

BRAHMS

The seminal and traumatic experience of Brahms’ life—the slow and tragic death of his mentor and teacher, Robert Schumann (1810-1856)—left a permanent mark on him and his music, and contributed to his lifelong bachelor status. It also stoked a growing desire to lead, more and more, the life of a lone scholar (without interest in seeking a university post), relying on a tiny and shrinking group of friends for their reaction to and constructive criticism of his music. This was unusual, considering his enormous success as a composer and performer.

The center of Brahms’ little circle and his towering musical inspiration was Robert Schumann, but after Schumann died it was largely limited to Robert’s wife, famous pianist Clara Schumann (1819-1896), and violinist and composer Joseph Joachim (1831-1907). When Joachim gave up composing later in life, Brahms felt that Joachim was no longer helpful, leaving him only Clara.

Brahms, a native of Hamburg, came to the Schumanns in Düsseldorf at age twenty with a letter of recommendation from Joachim. Just as Schumann had launched Chopin's and Berlioz’s careers with rave reviews in a newspaper for new music (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, cofounded by Schumann himself), he helped start Brahms' career by writing in a review that Brahms was “destined to give ideal expression to the times.”

Brahms may have been originally attracted to the Schumanns because they seemed more in line with his lower-class ancestry and the opposite of Franz Liszt (for whom he also auditioned) and Richard Wagner, with whom he was uncomfortable because of their perceived pretensions to royalty.

Soon Brahms became not only Robert Schumann’s favorite pupil, but also babysitter and member of the family. It was a complete surprise when, only one year later, Schumann (suffering from late-stage syphilis and not from any mental illness, as was once thought) threw himself off a bridge and was committed to an asylum. Clara’s feeling for what Robert then went through for the next two years is shown when, twenty-five years later, she wrote of her son Felix dying in an insane asylum, describing it as the experience of being buried alive.

In the asylum, Robert Schumann continued to compose, to write letters to Clara, and to take long walks with Brahms, during which they discussed all manner of profound musical topics, as before. About eight months before his death in 1856, Robert Schumann appeared to be in remission, and hope grew that he would return home. It was not to be.

Brahms’ personality from the beginning was that of a scholarly introvert, whose sometimes unexpectedly brusque manner often made him seem unsociable. An example of Brahms’ dry and hardly ingratiating wit is an anecdote about him trying out one of his cello and piano sonatas with a young cellist. Brahms kept playing louder and louder, until the cellist stopped to complain that he couldn't hear himself. “Lucky you,” Brahms replied.

Paradoxically, despite Brahms’ inability to make easy conversation, his chamber music is dominated by brilliant conversation, especially in these three violin and piano sonatas, as the themes are passed back and forth between the instruments, each speaker—sometimes waiting until the other is done, sometimes unable to resist jumping in as an interruption—gaining energy, inspiration, and passion from the other, until the music almost explodes in a whirlwind, or dies in high-drama tragedy.

After Robert Schumann’s commitment, Clara decided—in order to support her family—to restart her piano performing career; it had been put on hold while she’d had one child after another during the Schumanns’ ten-year marriage. Brahms at the age of twenty enjoyed filling in as a father figure to the children and organizer of the household. Such intimate involvement in the household and proximity to Clara gave him the opportunity to fall in love with her, although she was fourteen years his senior. They hid all evidence of their attachment in public, and it can only be guessed at from the few surviving letters.

A few days before Robert’s end, Brahms finally brought Clara to the asylum, to reunite Robert and Clara after the long, two-year separation. Brahms wrote “Surely I will never again experience anything as moving as the reunion of Robert and Clara. At first he lay for a long time with eyes closed, and she knelt before him, more calmly than one would believe possible But after a while he recognized her, and also on the next day. Of course he had been unable to speak for some time already. One could understand (or perhaps imagine one did) only disconnected words. Even that must have made her happy. He often refused the wine that was offered him, but from her finger he sometimes sucked it up eagerly, at such length and so passionately that one knew with certainty that he recognized the finger.” Their friend Joachim arrived just four hours before Schumann died. The young Brahms’ growing love for Clara (and possibly a sense of guilt) can be seen in the salutations of the few surviving letters (mostly from Brahms to Clara) from the time of her separation from Robert:

“Dear Frau Schumann,. Honoured Lady! Esteemed Lady; Most revered lady; Dearest Friend;” (When Brahms wrote to Robert Schumann in the asylum at this time, he began the letter with “Most beloved friend”) “Dear Frau Schumann” (this came a few days after his letter to Robert Schumann) “Dearest friend; Deeply, loved friend; Ever lovely, lofty lady; My most beloved friend; On the evening a full moon was promised for us, Beloved frau Clara; My dear Clara, My beloved Clara—I wish I could write to you as tenderly as I love you, and give as much kindness and goodness as I wish for you. You are so infinitely dear to me that I can't begin to tell you. I constantly want to call you darling and all kinds of other things, without becoming tired of adoring you. If this goes on, I will eventually have to keep you under glass, or save money to have you gilded.”

After Schumann’s death Brahms withdrew from Clara, hurting her feelings; it is likely that he understood that she wanted no more children. She had been pregnant almost every year of her ten-year marriage to Robert. However, her children later related their opinion that if Brahms had ever proposed, she would have accepted. Their friendship continued on a more mother-and-son basis (Joachim himself, in a letter to Liszt, said that Robert Schumann had loved Brahms like a son), with frequent squabbles, which they always managed to patch up. Clara promoted Brahms’ piano works in performances all over Europe just as she had once promoted Robert’s. She also performed the violin sonatas with Joachim.

Brahms’ ease of working with independent voices in his violin and piano sonatas comes from his extensive scholarly studies. He became editor of a many composer anthologies at a time when Germany was turning them out at a great pace. In fact, this makes Brahms a modern composer, in that he had to deal with what would be the main influence on composition in the twentieth century—music history. As composers began to attain college music degrees, they became afflicted with college libraries containing the complete works of all the major composers. Nothing so overwhelming ever hindered Mozart or Beethoven, who knew mostly music of their contemporaries plus a few works by Bach.

Brahms gathered a personal library of scholarly collections normally found only in the reference sections of major libraries:

- the Bach Gesellschaft (complete works of Bach, filling several bookcases), whose society Robert Schumann had been an original founder of;

- the complete works of Handel, Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Schumann (for which Brahms and Clara were themselves the editors);

- many first editions of J.S. Bach, C.P. E. Bach, Scarlatti, Gluck;

- most works by Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, and Schubert;

- numerous scores and autographs by contemporaries such as Dvorak, Joachim, Bruch, Liszt, Wagner, Berlioz, and Strauss, and lesser composers.

Besides collecting music for his own study, Brahms at first edited individual pieces, then joined the editorial board that put out the complete editions of Handel, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann. The numerous notes he made in the margins of these collections, especially those of Bach, show how eagerly he studied them. After such an exhaustive immersion in other composers’ music, it’s a miracle he was able to come up with anything original.

Embarrassingly, for such a well-educated man and in spite of great efforts, Brahms failed to learn French or Italian, and never felt comfortable anywhere but German-speaking lands (he lived in Vienna). This kept him from visiting either Britain, where every other successful musician (including Clara) was touring, or, later in the nineteenth century, America.

After Robert Schumann’s death, Brahms’ works became far more characterized by resignation and longing, nostalgia, and sadness. This can certainly be heard in the three violin and piano sonatas, which were written long after the earlier Sonatensatz, (sonata movement, originally meant to be part of a multi-composer sonata, but ultimately published by itself) which is full of youthful vigor and innocence.

The standard violin and piano sonata had been an extremely popular form for home entertainment, for men and women to court each other socially. (The stereotype from Mozart’s time was of the man playing the violin and the woman at the piano.) This gave the form a hint of romance, which Brahms would have been well aware of and may have used to represent his and Clara’s love.

Violin and piano sonatas were one of the few forms of music to be a source of profit for music publishers since the time of Mozart and Beethoven. But Brahms’ violin and piano works are far too difficult for amateurs, and they represent not just a virtuosic but a musical tour de force, full of drama and passion, but with little of the humor or lightness of spirit which can be found in the Mozart and Beethoven sonatas, unless that lightness is tempered by nostalgia or ennui. Brahms knew that, in order to sell his beloved chamber music—the form of music he worked hardest on and held closest to his heart -he needed to establish himself with an orchestral work. For a long time he relied on the success of his German Requiem; despite his own attempts and the urging of friends, he was never able to write an opera. Brahms was always aware, and sometimes frustrated, that his own music was so serious in mood. But in the violin and piano sonatas, the seriousness is countered with many opportunities for warm, luscious sound from both instruments.

Despite their strong disagreements over editorial decisions in the complete Schumann edition they cooperated on, Brahms kept sending his works to Clara for her approval, up until her death in 1896. An example of the kind of formidable musician she was can be seen in an anecdote from a Frankfurt party in 1881 from the memoir of a friend: “Clara Schumann and Brahms had agreed to play a four-hand pianoforte arrangement of Brahms’ Tragic Overture, a work which had then just been published. Before sitting down, Brahms took aside Marie Wurm, a pupil of Clara Schumann, who had asked her to turn the pages, and said to her ‘When you come to page four you must be careful to turn two pages instead of one, because in this copy two have been printed twice by mistake.’ At the crucial moment, Clara Schumann, startled and angry, hastily turned back the page and thus avoided a breakdown. At the end she turned on Marie Wurm and reproached her for what she took to be carelessness, upon which the young girl burst into tears, explaining that she had acted under orders. Thereupon Clara Schumann scolded Brahms, saying, ‘Johannes, how could you do such a thing?’ ‘Never mind, Clara,’ answered Brahms, ‘I only wanted to see whether you knew it all by heart already’ Obviously, she did.”

Her last concert performance, in 1891, was of a two piano version of Brahms’ Haydn Variations.

The last movement of the first violin and piano sonata was Clara’s favorite, and she asked to have it played at her funeral. (Brahms died eight months later, having ceased composing.)

Like many of the melodies in Brahms’ violin and piano sonatas, the main tune in the last movement of the first sonata is taken from one of Brahms’ own songs, Regenlied. Clara referred often in letters to Brahms to this melody, calling it “my theme.” The motive is itself derived from the opening of one of Robert Schumann's greatest piano works, Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), which represents David's little gang (as in David vs. Goliath) as underdogs, in this case Robert and Clara—with Brahms and Joachim later added—against the world. Robert Schumann made sure to note in the first published edition that the opening two measures were a “motto by Clara Wieck” (her maiden name). So the melody in Clara’s favorite of Brahms sonatas was onginally by Clara herself, and comes from her Mazurka op. 6 no. 5 Thus when Clara played the sonata with Joachim, she completed the circle she had been a part of most of her life, from Clara, to Robert, to Brahms, and back again to Clara.

Partial bibliography:

Quotes from letters: Johannes Brahms Life and Letters, edited by Atrya Avins

On Brahms' character: A Brahms Reader, by Michael Musgrove

Quotes from Joachim: Letters from and to Joseph Joachim, translated by Nora Bicidey

Music: The Compleat Brahms, edited by Leon Botstein

Notes by Peter Arnstein

NOTES FROM THE VIOLINIST:

This is likely the last CD that I will produce. At age 61, the practice demands combined with other life responsibilities have made it impossible for me to continue in this way and maintain the required high standards. Peter Arnstem and I have been a duo for more than 25 years. I am extremely fortunate to have had an artist of his magnitude and a gentle, kind friend whose personality never distracted from the challenges of learning and performing and recording this great repertoire. It has been a wild and unlikely career for both of us. Thank you, Peter.

This is the least challenging disc that we have ever produced, in that the Brahms sonatas were all previously recorded separately. At age 44, for sonata no. 1 in G Major, my vibrato was fast and consistent, and this recording (on my 'Spanish' Stradivanus) of a piece which perfectly suits me is one of the best recordings Peter and I have made. Russ Borud, the engineer, always produced a warm, engaging sound using analog technology. Sonatas 2 and 3 were recorded on the 1720 Ex-Rochester Stradivarius.

The second movement from Sonata no. 2 is one of the great examples of Sehnsucht, one of my favorite German words, which expresses the tension of man's heavenward reach toward perfect resolution in the divine, but has all the tension of near resolution, which is as close as we can get in this life—the pain of life, love, the pursuit of excellence, happiness, the raising of children, and work. This glorious composition causes one to reflect and dream "Someday I'll wish upon a star and wake up where the clouds are far behind me, where troubles melt like lemon drops away above the chimney tops, that's where you'll find me. Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly. Birds fly over the rainbow- -why, oh why can't I?” (Lyrics by Yip Harburg)

- Michael Antonello

NOTES FROM THE PIANIST:

It has been a thrill to play these Brahms sonatas, written after his violin concerto, relatively late in his life; the exhilaration goes beyond equivalent works by Beethoven or Mozart. In Beethoven, one is always aware that many of his violin and piano works don't have quite the polish or passion of his piano sonatas, symphonies, and string quartets, and in Mozart, the sonatas either lack attention to the possibilities of the two instruments that he showed in his violin or piano concertos, or lack the more expansive expression of his operas. In contrast, Brahms seems to have poured everything he had into these sonatas; they are in no way inferior to anything else he wrote. Similarly, Mike's Brahms interpretations reflect years of fermentation—making it all the more rewarding to have played and recorded these gems with him.

Brahms' piano parts in his instrumental sonatas make strange and awkward demands upon the hands. I struggled with them in college, and I could never have made a CD like this until I studied the two piano concertos; in conquering those, everything else by Brahms became technically far easier, which meant I could immerse myself entirely in the music; and the ocean of ideas that Brahms has here committed to paper is large enough to swim in forever.

- Peter Arnstein

MICHAEL ANTONELLO, VIOLIN

Before launching an international solo and recording career, American-born Michael Antonello attended both the Curtis Institute and Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, where he worked with Franco Gulli. He has served as concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony, an orchestra in Aspen, and the Rochester Symphony Orchestra in Minnesota. He also held temporary tenure with both the Minnesota Orchestra and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. He has soloed with the Erato Chamber Orchestra of Chicago, the Rochester Symphony, the Chelsea Symphony, Milano Classica, the Romanian Philharmonic, and St. Petersburg's State Capella Orchestra. He has toured extensively in recital with pianist Peter Arnstein; they have seven CD's to their credit.

Mr. Antonello has recorded many violin concertos including Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch g minor, Bruch Scottish Fantasy, Dvoràk, Vieuxtemps, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Saint-Saëns no. 3, and Glazunov with conductor Philip Greenberg and the National Orchestra of the Ukraine; and Mozart concertos No. 3 and No. 5 with Milano Classica. Antonello and conductor Richard Haglund have recorded the two Bach violin concertos, the Bach double, and Vivaldi's Four Seasons with the Erato Chamber Orchestra. A recent recording of the complete solo violin works of Bach has garnered a rave review from Gramophone: This is the kind of honest, decent playing that Bach must have heard in his mind when he wrote his music for solo violin. reflective, reminiscent, feeling the instrument surge under his hands…deeply personal … [Antonello] chisels out of the score an energy and passion that create a hypnotic melisma.

PETER ARNSTEIN, PIANO

Dr. Arnstein is well known in the Twin Cities area as a pianist and composer. He has often served as pianist and harpsichordist with the Minnesota Orchestra, and has accompanied many members of the Twin Cities' two main orchestras and college music faculties. A winner of international competitions in both composition and piano, he has toured the Midwest as pianist and composer-in-residence for the Sylmar Chamber Ensemble and currently teaches at the St Paul Conservatory of Music and the Evergreen School for the Arts in Edina. He has performed many times at the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland, as both piano soloist and harpsichord soloist. His CDs include programs from his own solo piano concerts, including Live from Edinburgh, Live from Illinois, and Hypnotico (British Columbia), as well as numerous CDs of his own compositions.

He received his doctorate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, his Master's from the University of Illinois-Urbana, and his Bachelor's from the Manhattan School of Music. His music is published by Manduca Music Publications in the United States and by Spartan Press in Europe.

He also writes liner notes for music CDs, science articles for ehow.com, classical music articles for examiner.com, and, in his spare time, short stories and novels.

PROGRAM

Sonata No. 1 in G Major, opus 78 (1979)

Vivace, ma non troppo 10:19

Adagio 7:07

Allegro molto moderato 8: 17

Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Op. 100 (1886)

Allegro amabile 8:36

Andante tranquillo - Vivace - Andante - Vivace di più - Andante — Vivace 6:33

Allegretto grazioso (quasi andante) 5:27

Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 100 (1888)

Allegro 7:47

Adagio 4:25

Un poco presto e sentimento 2:58

Presto agitato 5:55

Sonatensatz, Woo2 (1853)

Scherzo - Allegro 5:49

Total running time 71:13

TRIO DI VITA

“Trio di Vita - Though, strictly speaking, this performance of Peter Arnstein’s Scottish Fantasy wasn’t its World Premiere (that had happened the previous night at St Cecilia’s Hall), it roundly deserves its mention here. Arnstein had written it specifically for the Trio’s debut visit to the Fringe 2003.

The cello started it off with a melody “loosely inspired,” in the composer’s own words, by Gordon Jackson’s song in the movie “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.” The violin joined it very soon after with lively Niel Gow-like fiddling accompanied by the piano and cello. For eight minutes Arnstein “purposefully wove into the plaid fabric of the composition... the bowings and rhythms of Niel Gow,” incorporating dances such as jigs, reels, and a strathspey.

It was a delightful piece, crying out to be heard over again, an American eye on Scottish music, not a recreation of traditional Scottish music. It was a little too smooth for that, lacking in the Scottish bite and attack; the dance tempi, according to a member of the audience, “set by somebody who’d never danced the dances” It was a wonderfully, bright, spanking new musical tartan compliment.

Though 2003 is the Trio’s debut appearance, Michael Antonello and Peter Arnstein received rave reviews in the 1995 Fringe. They truly deserve rave reviews this year too. Theirs was a very polished, musically immaculate trio, deeply imbued with musical taste, and with a feeling of having played chamber music together for many years. In fact, the Trio was only formed this year, though all are old friends living very busy- and different - professional lives far apart from each other.

The whole programme was a real delight. The late much-loved Dr. Hans Gal, who’d been taught by Brahms, would have thoroughly approved of their Brahms Trio in the very hall where he himself made so much music.”

“Trio di Vita - As a violinist myself, to sit less than three feet away from the most amazing performer I have ever seen was a true privilege, Michael Antonello plays with an intense energy and passion that has filled me with inspiration. His rendition of Fritz Kreisler’s music blew me away with its technical brilliance and assurity. Pianist Peter Arnstein’s performances were marked by a mixture of sensitivity and extreme emotion which was most apparent in his own composition, the quirky Trio Jazzico Nostalgico. The trio’s competence was fully realised in Beethoven’s Trio in E Flat Major where each performer came into their own, whilst Mendelssohn’s Trio in D Minor was a true delight and a fitting climax to an outstanding evening.”

Trio di Vita - Debut

Trio di Vita’s debut recording celebrates its triumphant success at the 2003 Edinburgh Festival, where it performed all the music on this album in six concerts at St. Cecilia’s Hall and Reid Hall at the University of Edinburgh. Two works written for the occasion by composer Peter Arnstein were premiered at that event, and they receive their recorded premieres here.

Michael Antonello and Peter Arnstein have performed at the Festival several times, to great critical acclaim; much of their violin and piano repertoire has been recorded on MJA recordings.

Trio di Vita sprang into existence in the Spring of 2003, when violinist Antonello called up his old boyhood friend, cellist Scott Adelman, now residing in New Jersey, and asked him to come perform trios at the Edinburgh Festival. Though they hadn’t played together in twenty-odd years and were now conveniently separated by a thousand miles (Rehearse? How? In a plane?), in a split second of lunacy, Scott said yes.

Mr. Adelman was a late blooming child prodigy, starting cello lessons at the ripe old age of thirteen, but he made up for lost time by learning most of the cello repertoire in two years, performing his debut with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra at age fifteen.

At age seventeen he was accepted into the most exclusive music school in the United States, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and he also took master classes with cellists Gregor Piatigorgsky, Janos Starker, and Leonard Rose.

While at Curtis, Scott began to indulge his lifelong interest in flying. By eighteen he had his commercial pilot’s license, and worked as a pilot full-time at age twenty. Captain Adelman has been flying all over the world for Continental Airlines for eighteen years, and has performed cello and piano concerts all over the U.S.A. He also substitutes frequently with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and even conducted it a few years ago.

Michael Antonello also trained at Curtis, was concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony and the Rochester Symphony in Minnesota, and has performed with the Minnesota Orchestra. His three CDs with Peter Arnstein received rave reviews in Fanfare Magazine, he is beginning a project to record the complete Beethoven and Brahms sonatas, and he is well on his way to recording all the charming Viennese works of his idol, violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler. When he manages to put down his 1720 Stradivarius (a difficult thing for him to do), Michael is chairman of Wealth Management Advisors, a life insurance and estate planning firm.

Peter Arnstein earned his doctorate in piano from the University of Wisconsin- Madison and currently teaches at the St. Paul Conservatory of Music. He has won prizes in several international piano competitions, the first being the Watford Music Festival in England, where judges heard 22 eleven-year-olds each play Knecht Ruprecht by Schumann. The next day the judges all had themselves committed to mental institutions, but not before awarding first place to Peter. In 1992 he won Gold Medal in all categories at the Roodepoort International Composition Competition for his Orchestral Variations on a Theme by Mozart. In between he became a well-known chamber musician in Minneapolis, performing with many members of the Minnesota Orchestra and St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. He has performed solo concerts in the U.S.A. and Great Britain on both piano and harpsichord, and has composed more than a hundred chamber music works. In his spare time he writes romantic-suspense novels and constructs model railroad empires in his basement.

All the trios on this recording represent the composers’ first efforts in the genre, with Beethoven trying especially hard to put his best foot forward, as it was his first published composition, at age twenty-three. Mendelssohn was an old hand at chamber music by this point, having long ago startled the music world with perhaps the most beloved chamber music piece of all time, the Octet, written at age sixteen. Brahms’s trio is both a young work and an old one, extensively revised in his sixties.

Trio Jazzico Nostalgico was written especially for Trio di Vita, filling a gaping hole in the repertoire, being both short and a little more light-hearted than the other three full-throated trios.

Scottish Fantasy is inspired both by the rhythms and bowings of the old Scottish fiddler Niels Gow, and by an old Scottish tune, Hey Johnny Kobe, as it was sung by Gordon Jackson in the movie, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The Scottish Fantasy is more virtuosic than the other works, and it also provides more of a showcase for the cello talents of Mr. Adelman, who is incapable of playing anything but “Scott”-ish music.

Trio di Vita looks forward to more performances in St. Paul, Philadelphia, and Edinburgh, and is working on a new recording of Schubert and Brahms.

All recordings were made at the St. Paul Conservatory, 2003

Recording engineer: Russ Borud

Mastering: Cara Mia Antonello, Scott Adelman

© 2004 MJA Productions, all rights reserved

CD Design & Layout: Bradley Reed

PROGRAM

CD 1

Trio in E-flat Major, Opus 1, no. 1 (1793) Ludwig Van Beethoven

Allegro 9:21

Adagio cantabile 6:08

Scherzo: Allegro assai 4:31

Finale: Presto 7:19

Trio in d minor, Opus 49 (1839) Felix Mendelssohn

Molto allegro e agitato 9:35

Andante con moto tranquillo 6:22

Scherzo: Leggiero e vivace 3:38

Finale: Allegro assai appassionato 8:00

CD 2

Trio in B Major, Opus 8 (1854, revised 1890) Johannes Brahms

Allegro con brio 10:19

Scherzo: Allegro molto 6:08

Adagio 7:49

Allegro 6:01

Trio Jazzico Nostalgico (2003) Peter Arnstein

Moderato Sentimentale 3:34

Allegro Awkwardito 1:54

Presto Scurrilissimo 3:12

Scottish Fantasy (2003) Peter Arnstein 7:56

TCHAIKOVSKY - GLAZUNOV VIOLIN CONCERTOS

TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN CONCERTO

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 -1893) was extraordinarily lucky in his depression. For years he’d been pondering marriage as a way to prevent the news of his homosexuality from spreading to his sponsors among the Russian nobility. When a female college student, a stranger, wrote to him expressing her overpowering love, he decided his prayers had been answered. But in spite of being a full-time music student, she had never heard a note of Tchaikovsky’s music, which was odd, because he was already a star, as well as a teacher at the Moscow Conservatoire; she had developed a crush on him entirely from glimpsing him at school. Within days of a hastily arranged wedding (he proposed the day after they met), he felt he could no longer hide his exploding antipathy toward her, of which she remained clueless. In Moscow he met her family and despised them on sight. In these situations, when he was unhappy and uncomfortable, his usual recourse was to ask a friend in another city to send a telegram stating that he was urgently needed elsewhere. He was soon on his way out of Russia, never to see her again, though he always supported her financially.

Despondent over the entire affair, which he now viewed as one colossal mistake (no biographer seems to care about the feelings of Tchaikovsky’s wife), he wondered what to do with himself, and how to force his mind back into composing. Nadezhda von Meek, who had recently made herself his benefactress and was the wife of a wealthy railroad magnate, came to Tchaikovsky’s rescue. She had always been in love with Tchaikovsky’s music but had refused to meet him, afraid that the man in the flesh might puncture the picture that his music had conjured in her mind. During the following decade of her support, they kept up a voluminous correspondence with each other, revealing intimate details of their lives and feelings. (When her fortune finally dried up, so did his letters.) Tchaikovsky had hardly been doing poorly before this van Meek fairy godmother came into the picture. He already had one servant, who was able to cook only one dish, cabbage-soup and groats. But Tchaikovsky was well satisfied with this, needing no more stimulation than his own talent. Von Meek was a luxury.

In his postnuptial mood of dejection, Tchaikovsky asked von Meek for money to travel. While his salary at the Moscow Conservatoire continued, Tchaikovsky played hooky and fled to Berlin, then Paris. (He sent his wife to his sister’s house to be supervised, to make sure she didn’t spill the beans over what kind of man her husband was.) He continued on to Lake Geneva; after his brother joined him there, he decided Italy was the place to be. He visited Florence for two days, then Rome. After a couple of weeks, and having had his fill of statues, he arrived in Venice. Nine days later came Vienna. What a wonderful way to buck one’s spirits back up! Five weeks more in San Remo, Italy, then Pisa, back to Florence, finally settling in the small Swiss village of Clarens, where Stravinsky would write his Rite of Spring, 35 years later. To support all these travels, Tchaikovsky needed numerous infusions of money, and von Meek obliged with each request. If only all sufferers of depression could be so lucky! Von Meek could not really afford these extra subsidies, but when she was told that Tchaikovsky had rejected his wife and the marriage was a sham, she was overjoyed —she would remain the only woman that Tchaikovsky would ever be loyal to.

In Switzerland, Tchaikovsky played through Lalo’s new violin concerto, Symphoniè Espagnole, with his visiting friend and pupil (and possibly lover), violinist losif Kotek. Kotek had been studying in Berlin with Joseph Joachim, the violinist who lent a helping hand to nearly every composer of great violin works during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Written in 1878, Tchaikovsky's violin concerto burst out of him at lightning speed—the first movement in five days, the last in three. Tchaikovsky and Kotek parted ways when Kotek refused to premiere it. Tchaikovsky then rededicated it to Leopold Auer, a violinist who was as much a mentor to composers of violin music in Russia as Joachim was to the rest of Europe. But Auer rejected it when he first saw the score, so it was rededicated once again, this time to the violinist Adolf Brodsky, who premiered it in Vienna. Auer eventually changed his mind about the concerto, especially after he arranged his own version, and he went on to made the concerto a great success, teaching it to his two pupils, Jascha Heifetz and Nathan Milstein. In his later years, Auer moved to America, to spend his twilight years (after 1927) teaching at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where Antonello studied.

At its premiere in Vienna, Tchaikosky’s violin concerto was poorly received by the leading critic of the day, Eduard Hanslick: “The violin is no longer played: it is tugged about, torn, beaten black and blue ... We see a host of gross and savage faces, hear crude curses, and smell the booze ... Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto confronts us for the first time with the hideous idea that there may be musical compositions whose stink one can hear.” Hanslick was known, however, for his bias against Slavic music. The American composer Edward MacDowell said: “Tchaikovsky's music always sounds better than it is; the music of Brahms is often better than it sounds.” By which he may have meant, Brahms is more fun to play, Tchaikovsky more enjoyable to hear.

GLAZUNOV VIOLIN CONCERTO

Glazunov’s violin concerto was written in 1904, and, like the Tchaikovsky concerto, was also written for and dedicated to Leopold Auer. Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936), whose principal teacher was the great Russian orchestrator, Rimsky-Korsakov, is now mainly remembered as a teacher of Shostakovich, who greatly admired his teaching, even though Glazunov spent many of their lessons sitting behind a desk, sipping through a long straw from a bottle of vodka hidden in a partially open drawer. Glazunov was much beloved and known for going out of his way to help students at the St. Petersburg Conservatory (where Tchaikovsky had studied). When the authorities of the Russian government offered to increase his salary, he cleverly arranged that the money instead be spent on firewood for the suffering students. He made himself a firewall betweenJewish students and the powers that be, enabling violinists Jascha Heifctz, Nathan Milstein, and Mischa Elman, who would go on to become the leading violinists of their time, to enroll at the conservatory

Although Glazunov’s violin concerto is often listed as being in three movements, it is, in fact, unique in the violin concerto repertoire for being in one long, extended movement. (The Chausson Poème is one movement, but it is much shorter and more analogous to one movement of a standard concerto.) Other violin concertos such as the Mendelssohn have links between the movements, but these can be easily cut if the performer wishes to perform only one movement at a time; in any case, the movements do not share any motivic material, the way the various sections of the Glazunov do. The Glazunov thus has more in common with Liszt’s piano sonata, which is often talked about as if it had separate movements, when, in fact, the music never pauses or loses intensity from beginning to end, and cannot be cut in any way.

Notes by Peter Arnstein

MICHAEL ANTONELLO

Michael Antonello attended the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia as a student of Jascha Brodsky, followed by studies at Indiana University where he worked with concert violinist Franco Gulli. He was also engaged as an orchestral and chamber musician at the Mostly Mozart Festival in NY Following his studies, he was appointed concertmaster of the Grand Rapids Symphony. In addition, he has served as concertmaster of the orchestras of the Aspen Music Festival, and the Rochester Symphony Orchestra in Minnesota and held temporary tenures with both the Minnesota Orchestra and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. Mr. Antonello has recently been a featured soloist with the Erato Chamber Orchestra of Chicago, the Rochester Symphony, Milano Classica, Romanian Philharmonic, and St. Petersburg’s “State Capella Orchestra”.

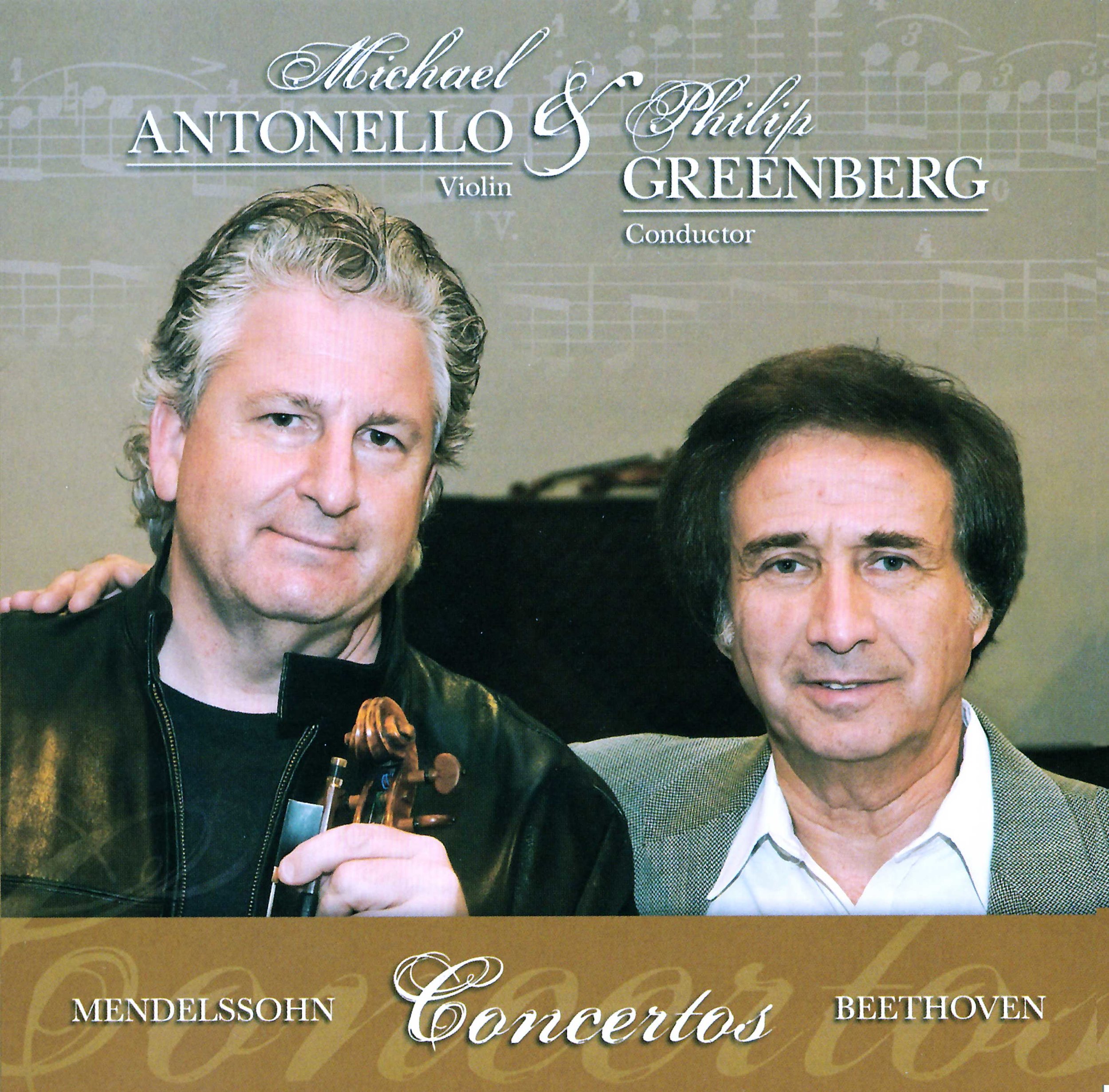

Antonello has also performed extensively in recital with pianist Peter Arnstein, including regular performances at the Edinburgh Festival. Together they have recorded seven CDs, which include much of the standard Sonata repertoire, as well as favorite violin showpieces. Mr. Antonello has recorded many violin concertos including the Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruch with conductor Philip Greenberg and the National Orchestra of Ukraine. They have also recorded Mozart Concertos No. 3 and No. 5 with the Milano Classica Orchestra. He and conductor Richard Haglund have performed concerts in Chicago, St. Petersburg Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Moldova. In 2009, Michael Antonello co-founded the Southern Tuscany International Festival of Music, Literature, Food, and Wine.

He plays the 1720 “Ex-Rochester” violin made by Antonio Stradivari. Crafted during the “Golden Period”, when his genius was the most focused and productive, this instrument is a supreme example of the maker’s finest tonal quality. It is referenced in no fewer than five books dedicated to Stradivari’s work.

PHILIP GREENBERG

Philip Greenberg is currently the Artistic Director and Conductor of the Kiev Philharmonic, a position he has held since 2003. He also serves as the Music Director and Conductor of the Royal Festival of the L'Eté Musical Dans la Vallée du Lot in Cahors, France. Maestro Greenberg has also recently been named Artistic Director and Conductor of the Tuscan Music Festival of the Milano Classica Orchestra of Italy.

For 18 seasons Philip Greenberg was the Musical Director/Conductor of the Savannah Symphony, where under his leadership an unprecedented level of national and international acclaim attracted the world’s most renowned soloists including Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zuckerman, Isaac Stern, Joshua Bell, Franco Gulli, Phillipe Entremont, and Janos Starker.

Maestro Greenberg served as Assistant Conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Resident Conductor of the Phoenix Symphony, and Music Director of the Fresno Philharmonic in California. A frequent and popular guest conductor, he has appeared on podiums in Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, France, Germany, Austria, Russia, Uruguay, Mexico, Brazil and Italy as well as Chicago, Phoenix, Santa Barbara, El Paso, Colorado, Indiana and Michigan. He has recorded extensively with the Bayerisches Kammerphilharmonie and the Kiev Philharmonic and has performed in many of the world’s greatest concert halls, including a live televised broadcast from the famed Mozarteum of Salzburg Maestro Greenberg launched his international career as the double winner of the Nicolai Malko International Conducting Competition in Copenhagen. He remains the only conductor in the fifty year history of the competition to win not only the judges prize but the coveted Orchestra prize voted on by the musicians of the Danish Radio Orchestra.

NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA OF UKRAINE

Established in 1937, the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, formerly known as the Ukrainian State Symphony Orchestra, is recognized as one of the most accomplished symphonic ensembles of the former Soviet Union. President Leonid Kuchma declared the orchestra’s change of status in mid-1994 reaffirming its reputation as Ukraine’s premiere orchestra. During the past five decades, the orchestra has worked under a number of this century’s most recognized conductors and distinguished soloists including Emil Gilels, Leonid Kogan, Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, Sviatoslav Richter, Mstislav Rostropovich, Artur Rubinstein and Isaac Stern.

© 2011 MJA Productions

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine

Conductor: Philip Greenberg

Producer: MJA Productions

Producer: Alexander Hornostai

Engineer: Andrij Mokrytsky

Editing: Viacheslav Zhdanov & Andrij Mokrytsky

Booklet Notes: Peter Arnstein

Photography: John Walsh, Hearthtone Video & Photo and William Scott (Violin Maker, Photographer)

Graphic Design: Imaginality Designs, LLC

PROGRAM

Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-1893): Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D major, Op. 35

Allegro moderato 19:44

Canzonetta. Andante 6:56

Finale Allegro vivacissimo 10:14

Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936): Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 82

Moderato - Andante - Allegro 21:44

Total running time 58:45

SALUT D’AMOUR

“Antonello is a poetic player.”

“In fact it would be hard to better Antonello’s violin playing anywhere on the Fringe…And not only is Antonello a joy to listen to, but also to watch, especially when he rises on tiptoes to reach top notes.”

“…if Arnstein’s fingers were nimble, his perceptions were crisper still…”

“Antonello is accompanied by an excellent pianist …who has improvised here a marvelous accompaniment to the Leclair Sonata …I was enchanted by Arnstein’s ornate new accompaniment.”

ABOUT THE ARTISTS & THE ART

Michael Antonello aspired to a musical career as a youngster and received excellent training in Minneapolis with Mary West, a nationally recognized violin teacher. He later studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and at Indiana University with Franco Gulli. Five to six hours of practice daily during these years helped him establish a firm technical foundation that later served him well during lapses in his music career.

Michael Antonello is also a nationally recognized leader in the insurance business. The year this recording was made (1992) he was the second leading agent in the world for Sun Life of Canada, one of the largest insurance companies in North America. He qualifies almost every year for the Top of the Table, a group composed of the top 3% of the most productive agents in the world. In 1990 Michael and his wife Jean were the main platform speakers for this presti- gious organization.